Click Here to Return To Milestones Vol 1 No 2

Click Here to Return to Milestones Vol 1 No 3

This paper was originally presented at the County Historical Symposium in October, 1974. Mr. Palmquist is a second year law student at Pitt.

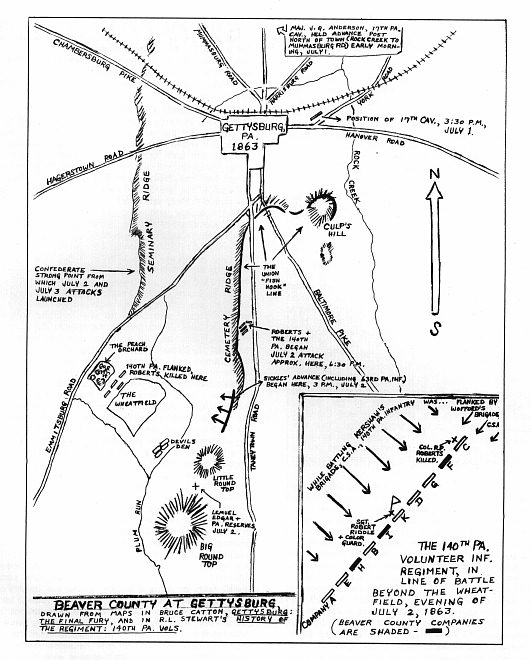

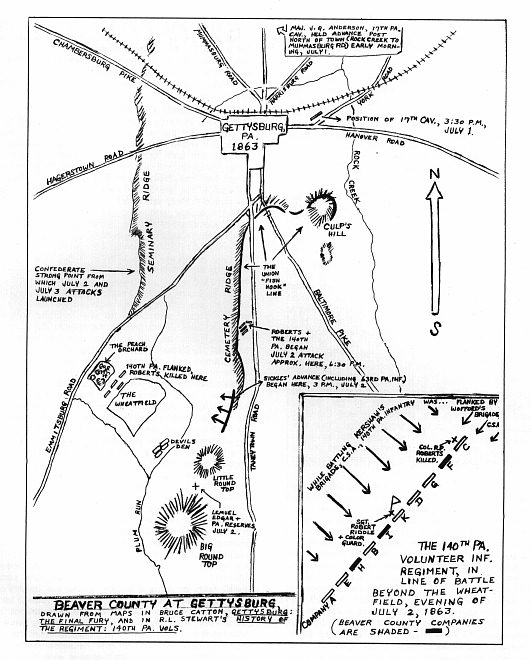

June 30, 1863. About 4,000 cavalrymen in Union blue, members of the Army of the Potomac's 1st Cavalry Division, are patrolling the many roads leading into the little country town Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Miles to the south of the blue horsemen is the rest of the Army of the Potomac, under its new commander, General George Meade. To the north are elements of General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia, which has invaded the Keystone State.

"The night of the 30th was a busy night for the division," the cavalry leader General John Buford wrote. "No reliable information of value could be obtained from the inhabitants, and but for the untiring exertions of many different scouting parties, information of the enemy's whereabouts and movements could not have been gained in time to prevent him from getting the town before our army could get up.."

Among Buford's nighthawks prowling the roads in search of the Confederates was Sergeant Joseph E. McCabe, of Bridgewater. The twenty-two year old sergeant was a member of the 17th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment's Company A, an outfit the home-folks in Beaver County still referred to as the "Irwin Cavalry," the name given the troopers upon enlistment, and before their incorporation into the 17th Regiment. It had been several days ago, in Maryland, McCabe recalled, that he and other Pennsylvanians "!earned that General Lee was marching into our native state. Buford's men had been pushed ahead of the rest of the Union army, to probe for the enemy, and had entered Gettysburg at about noon on June 30th. "Our band," McCabe said, "struck up one of the national airs, while the citizens cheered us on with a will, and helped us to pies and cakes, which they could hand to us as we passed through."

Now, on the roads north of town, two of McCabe's boys turned up something. Corporal John Mowry and Private David H. Niblo managed to capture a Rebel whom they sent back to headquarters for questioning. As a result of such efforts, General Buford by 10:30 that night knew the approximate whereabouts of two of the three Confederate Corps. The knowledge was not comforting, since Buford with 4,000 cavalry was facing the bulk of Lee's army. When a subordinate assured the cavalry general that he could handle any number of the enemy, Buford retorted:

"No, you won't. They will attack you in the morning, and they will come 'booming' - skirmishers three deep. You will have to fight like the devil to hold your own until supports arrive." Buford simply hoped to - in his words - "entertain" the enemy till the main body of the Union army was able to reach the place.

Commanding the far picket line from Rock Creek to the Mummasburg Road was young Major James Quigley Anderson of the 17th. Born in Brighton Township, and a civil engineer before the war, Anderson had been mustered in as Company A's lieutenant, had become its captain when Captain Daniel Donehoo had resigned, and had held the rank of Major less than a month. His health was not yet broken. Two more years of war would do that, and he would go home to die, about six months after Appomattox, of what doctors then called "pulmonary consumption." This night he waited outside Gettysburg for the Rebels to "come booming" down the roads.

At about 5:30 on the morning of July 1, the gray infantry came. Anderson, spotting their advance parties, sent a rider galloping back to inform his superiors, then dismounted his men. All along the Union line others did the same. By 8:00 the enemy was on them in earnest. "They got too many for us," Sergeant McCabe wrote later, "and we were compelled to dismount and use the stone fence for breastworks, which we did with telling effect." Shooting from cover with their new Spencer carbines, the cavalry put up a bold front to make the Rebels believe they faced more than 4,000 men.

And the cavalry held. In response to Buford's messages, General John Reynolds, himself a Pennsylvanian, rushed his First Corps to the firing line. Reynolds, killed shortly after relieving Buford's men with his infantry, has generally been regarded as "the architect of the battle." One of Reynolds' own aides remarks that "Buford and Reynolds were soldiers of the same order, and each found in the other just the qualities that were most needed to perfect and complete the task intrusted to them. The brilliant achievement of Buford, with his small body of cavalry.... is but too little considered in the history of the battle of Gettysburg. It was his foresight arid energy, his pluck and self-reliance, in thrusting forward his forces and pushing the enemy, and thus inviting, almost compelling their return, that brought on the engagement of the first of July."

The battle grew in intensity, as more and more troops, Union and Confederate, came up. Anderson, McCabe and the other Beaver Countians with Buford moved rapidly from point to point as they were needed. "We were now ordered to the right of the town," McCabe says, "and fought there for some time, mounted and dismounted, and quite a squad of us got into an old brick church and fired from the windows for a short time. We then returned to our horses, remounted and fell back through the town, the Rebs following us up and taking possession of the town."

The fighting that day was desperate, with at least 16,500 Union and Confederate casualties. Around 4:00 p.m. "the whole Confederate line advanced to the final attack," and swept the Union forces from their positions, smashing them back south of Gettysburg to the famous "fishhook" defensive line on Cemetery Ridge and Culp's Hill. There, says the Union Chief of Artillery, "wood and stone were plentiful, and soon the ... line was solidly established. Nor was there wanting other assurance to the men who had fought so long that their sacrifices had not been in vain. As they reached the hill they were received by General Hancock, who arrived just as they were coming up from the town, under orders from General Meade to assume the command. His person was well known; his presence inspired confidence, and it implied also the near approach of his army-corps."

"Hancock's representations were such," writes a war correspondent, "that General Meade instantly gave orders for the forward movement and concentration of all the corps on Gettysburg, and he advanced his headquarters to that point, reaching it at one o'clock of the morning of the 2d."

A few hours later, a regiment in Hancock's Second Corps - the 140th Pennsylvania Infantry - was on the march to reinforce the Union position at Gettysburg. The 140th Regiment's commander had good reason to be tired, aside from the obvious one, the beginning of a march at 3:30 a.m. He was Colonel Richard P.

Roberts, 43 years old, in civilian life a lawyer. Until very recently he had been at his home in Beaver on sick leave. About a month before his doctors had written the authorities asking that the Colonel's leave be extended. "From present symptoms," they said, "he is in danger of being prostrated by Typhoid fever ... an attempt on his part to join his Regiment at this time would endanger his life." But, they had added, "His mind is ill at ease." News of Lee's northward advance had done nothing to ease Roberts' mind, but instead sent him hurrying back to the army. On the first leg of his journey, he had fallen ill again at Washington, D.C., a relapse terminated by what a friend called "one of the many revelations during the war, of the power of the will to dominate and subdue physical weakness and disease." A ride on a Potomac River canal boat followed by a 30-mile hike had reunited the ailing Colonel with his men on June 28. From there Roberts had kept on tramping with his regiment, in the advance

north which he termed "one of the greatest marches on record." Now, on this early morning of July 2nd, he and the 140th Pennsylvania were on the road to Gettysburg.

Companies F, H and I of the 140th comprised that regiment's Beaver County contingent. Among them was young Lieutenant William Shallenberger of Rochester, the regimental adjutant and Colonel Roberts' good friend. The equally youthful Captain Thomas Henry, Roberts' nephew, led Company F. He possessed, one of his soldiers declared, "the two grand requisites to make an efficient officer ... brains and energy." Sergeant Robert Riddle, Company F, carried the regiment's colors. Another of the color-guard, Corporal Joseph Moody, along with the rest of Company H, represented the Hookstown-South Side area. Lieutenant Thomas Nicholson had left the editor's desk of the Beaver ARGUS to serve with Roberts-, at the time, his printer's devil had complained in the columns of the paper that "the country seems to require all our able-bodied men and the next call may leave the ARGUS without even THE 'DEVIL.' "

Beaver Falls' Corporal Robert W. Anderson, Company 1, was not yet aware of how much soldiering one man could do in a lifetime, but he would find out before his death in 1916. This morning he was going to Gettysburg. He would fight through the rest of this war with the 140tth. And 35 years later, once again a Pennsylvania volunteer, he would be skirmishing with the Spanish outside Manila, in the Philippines.

About 8:00 in the morning of July 2nd, Roberts and his men joined the Army of the Potomac's line. The most compact description of the troop disposition of either side comes from a poem, Stephen Vincent Benet's JOHN BROWN'S BODY:

Draw a clumsy fish-hook now on a piece of paper, To the left of the shank, by the bend of the curving hook, Draw a Maltese cross with the top block cut away. The cross is the town. Nine roads start out from it East, West, South, North.

And now, still more to the left

Of the lopped-off cross, on the other side of the town,

Draw a long, slightly-wavy line of ridges and hills

Roughly parallel to the fish-hook shank.

(The hook of the fish-hook is turned away from the cross

And the wavy line.) There your ground and your ridges lie. The fish-hook is Cemetery Ridge and the North Waiting to be assaulted-the wavy line Seminary Ridge whence the Southern assault will come.

The valley between is more than a mile in breadth. It is some three miles from the lowest jut of the cross To the button at the far end of the fish-hook shank, Big Round Top, with Little Round Top not far away. Both ridges are strong and rocky, well made for war. But the Northern one is the stronger shorter one. Lee's army must spread out like an uncoiled snake Lying along a fence-rail, while Meade's can coil Or halfway coil, like a snake part clung to a stone. Meade has the more men and the easier shifts to make, Lee the old prestige of triumph and his tried skill. His task is-to coil his snake round the other snake Halfway clung to the stone, and shatter it so, Or to break some point in the shank of the fish-hook line And so cut the snake in two.

Meade's task is to hold.

That is the chess and the scheme of the wooden blocks Set down on the contour map.

Having learned so much,

Forget it now, while the ripple-lines of

the map

Arise into bouldered ridges, tree-grown, bird-visited,

Where the gnats buzz, and the wren builds a hollow nest

And the rocks are grey in the sun and black in the rain,

And the jacks-in-the-pulpit grow in the cool, damp hollows.

See no names of leaders painted upon the blocks

Such as "Hill," "Hancock," or "Pender"

,

but see instead

Three miles of living men-three long double miles

Of men and guns and horses and fires and wagons,

Teamsters, surgeons, generals, orderlies,

A hundred and sixty thousand living men

Asleep or eating or thinking or writing brief

Notes in the thought of death, shooting dice or swearing,

Groaning in hospital wagons, stand guard

While the slow stars walk through heaven in silver mail,

Hearing a stream or a joke or a horse cropping grass

Or hearing nothing, being too tired to hear.

All night till the found sun comes and the morning breaks

Three double miles of live men.

Listen to them, their breath goes up through the night

In a great chord of life, in the sighing murmur

Of whind-stirred wheat.

A hundred and sixty thousand Breathing men, at night, on two hostile ridges set down."

Upon the arrival of the 140th, says Lieutenant William Shallenberger, "all was quiet, save an occasional shot from our batteries... nothing alarming occurred during the day until three o'clock...

Before 3:00, Buford's cavalry had been withdrawn from the Federal line and sent to the rear. Thus ended the role of Company A, 17th Pennsylvania, in the battle of Gettysburg.

But events at 3:00 that afternoon saw other Beaver Countians entering battle. At that time General Dan Sickles, commanding the Union Third Corps, made his still-controversial move from the Cemetery Ridge line onto a new position to the west. A staff officer stationed near Roberts' men described how the move must have appeared to them:

"It was magnificant to see those ten or twelve thousand men-they were good men-with their batteries,... all in battle order, in several lines, with flags streaming, sweep steadily down the slope, across the valley, and up the next ascent, toward their destined position! From our position we could see it all. In advance Sickles pushed forward his heavy line of skirmishers, who drove back those of the enemy, across the Emmitsburg road, and thus cleared the way for the main body. The Third Corps now became the absorbing object of interest of all eyes. With the Third Corps in this advanced position was Company C, 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry, recruited in New Brighto ' n and led today by Captain George Weaver of Vanport. Weaver's men, with the rest of Sickles' corps and the entire Union left, was about to be hit by the hammer-blow assault of Longstreet's Confederates.

The attack burst on this salient just as Meade angrily confronted Sickles about the unauthorized move. Upon Sickles' offer to move back to Cemetery Ride, Meade snapped, "I wish to God you could, Sir, but you see those people do not intend to let you."

"Hitherto," a Union officer wrote, "there had been skirmishing and artillery practice-now the battle began; for amid the heavier smoke and larger tongues of flame of the batteries, now began to appear the countless flashes, and the long fiery sheets of the muskets, and the rattle of the volleys, mingled with the thunder of the guns. We see the long gray lines come sweeping down upon Sickles' front, and mix with the battle smoke; now the same colors emerge from the bushes and orchards upon his right and envelope his flank in the confusion of the conflict ... What a hell is there down that valley!"

The men of Company C of the 63rd fired into those "long gray lines" until Captain Weaver, along with the other company commanders, informed their Major that "our ammunition was about spent" and that soon "we would. have nothing but the bayonet." With that they were relieved by another regiment, while the battle raged unabated. The Round Tops were barely held for the Union. Sickles was battered by persistent assaults.

At this point, to aid Sickles' faltering lines, the Ist Division of Hancock's Second Corps was readied for an advance into the Wheatfield. Colonel Richard P. Roberts and the 140th fell in and prepared to move. But first came what an officer described as "one of the most impressive religious ceremonies I have ever witnessed" Father William Corby, Catholic Chaplain of the Irish Brigade, which would go into battle on Roberts' left, stood upon a rack and gave general absolution to his soldiers, many of whom were Irish immigrants. Roberts and his men removed their caps. "No doubt," their regimental historian says, "many a prayer from men of Protestant faith, who could conscientiously not bow the-knee in a service of that nature, went up to God in that impressive and awe-inspiring moment." Such was Father Corby's wish. "That general absolution was intended for all," he reported, "not only for our brigade, but for all, North and South, who were susceptible of it and who were about to appear before their Judge." The impromptu service ended, the advance through the Wheatfield began. Lieutenant-Colonel John Fraser, the Washington County professor who was Roberts' second-in-command, writes that the regiment "moved rapidly forward to engage the enemy." Shallenberger thought the Confederate fire "sounded like a hail-storm among the leaves and branches." Moving into and from a small patch of woods, the 140th, to use Fraser's words, "opened a brisk fire, which it kept up with great firmness and coolness, steadily driving the enemy before it until we reached the crest of a small hill." And there the advance stopped. The Wheatfield area was known as the "whirlpool" of this battle. In a flurry of small unit actions, troops were sucked in, flanked by fresh enemy forces appearing as if from nowhere, cut off from their supports, thrown back. Roberts saw his regiment about to be taken on its exposed right by some suddenly appearing Rebel troops, and stepped out to head them off. The regiment's historian noted his "pale set" face as he passed to the right, and heard his last words. The Beaver ARGUS would claim that he shouted:

"My brave boys, remember that you are upon your native soil, your own Pennsylvania. Drive back the Rebel invaders!" But the best that his soldiers themselves could recall were the words:

"Steady men."

"Fire low," and

"Remember you are Pennsylvanians."

And then he stumbled and fell, shot in the chest.

The Rebels, whose flanking movement the Colonel had sought to avert, came on and poured a terrific fire into the Union line. The fallen officer's body was hauled slightly to the rear, and Shallenberger, who felt that he had lost in Roberts "one of the strongest friends a man can have," scurried to Fraser to tell him the regiment was flanked.

For the 140th, it was now a matter of getting out the best they could. Their flag went down, as Sergeant Riddle the color-bearer was shot and fell upon it. Corporal Joe Moody rescued it and handed it to another soldier, while he attempted to care for the severelywounded Riddle.

Alven Greenlee and his cousin John C. Gibb both fell mortally wounded. As the regiment retreated, Shallenberger was hit in the leg. He tried to stump along using his sword for a cane, but couldn't make it. He waved those who tried to help him on as the enemy pressed them closely, but two of the Hookstown boys refused to leave him. The Rebels scooped them up and placed under guard in a little log house nearby. "Visions of Southern prisons flitted before us," Shallenberger recalled later.

From the Round Top area, Private Lemuel G. Edgar of Darlington watched the' retreating Union troops, "firing and falling back, firing and failing back, their front diminishing at every volley." Edgar, who, the local paper testified, was "a good and brave soldier," belonged to Company F, 10th Pennsylvania Reserves. The Reserves were a proud outfit, an all-Pennsylvania division which had fought since 1861 in practically every engagement the Army of the Potomac had participated in. Besides Edgar and Company F, which was captained by Abner Lacock, two other Beaver County Reserve Companies, K of the 10th under A. M. Gilkey and H of the 9th Reserve Regiment under Captain Jacob S. Winans, "looked down the western slope of Little Round Top" to see that "the skirmishers of the enemy were almost at its foot and his somewhat broken and disordered but exultant lines not far in their rear."

The 9th and 10th Reserves formed a defensive line on Little Round Top, while others of the Reserve charged down to hit the enemy. General Crawford, leading the Reserves' charge, reported that "two welldirected volleys were delivered upon the advancing masses of the enemy, when the whole column charged at a run down the slope, driving the enemy back across the space beyond."

Edgar, Lacock and the others watched the downhill charge from where they anchored the line, while William Shallenberger, in that "space beyond," listened and watched with growing anticipation. A soldier near where Shallenberger was confined has described the charge as Roberts' young friend must have seen it. He first heard, the soldier recounts, "the solid, ringing, regular tramp of firm, determined men. Concealed by the smoke and the irregularities of the ground, the sound of the approaching mass was heard before the line appeared in sight. As it drew nearer and nearer, that splendid division, the Pennsylvania Reserves, came suddenly into view, sweeping everything before it, as if confident in the assurance of its own inherent strength. With Crawford leading, hat in hand, waving his followers on to victory; with fixed bayonets, steady tread and in excellent alignment, shouting and cheering, as if the victory were already theirs, they swept on in that memorable charge that restored so much of the ground lost and recovered so many of the guns taken during the afternoon. Their rush had been so sudden that many of the enemy, who had succeeded in working around the right ... were caught between their advancing and Barnes' retiring lines. There was no escape..." The Reserves' advance spelled escape for Shallenberger, however. "Back in hot haste come the rebels," he said of the move.

"They pass us by, not even calling off our guards who fall willingly into our hands, prisoners of war ... Never was the old flag more welcome. Darkness closed in upon the field of carnage, and the sickening story of the Wheatfield, the brilliant rescue of the Round Tops, had passed into history. "

History records a third day's fighting at Gettysburg. July 3 saw Pickett's famous charge, and an end to the battle. But for the most part, active fighting by Beaver Countians ended with the actions of July 2nd. On July 3rd, the 9th and 10th Reserves helped strengthen the Union hold on the Round Tops. The 140th Infantry, which had lost about half its strength in the "Wheatfield Whirlpool" on the 2nd, faced the "severe and longcontinued artillery fire which the rebels opened" before Pickett's charge without losing a man. George Weaver and C Company of the 63rd, who had fought until their ammunition was gone the day before, remained "just to the right of Little Round Top" until after Picket's charge, "when we were taken at a double-quick down the line, and halted in front of where Pickett had been repulsed."

At 6:00 p.m. on the evening of July 3rd, the 139th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment pushed out into the position Sickles had taken on the 2nd, and recovered several cannon which Sickles had abandoned. Company H of the 139th, partially recruited in Beaver County, lost two men in this little action, one of whom, Private William Carter, was captured and died almost a year later in the dreaded Rebel prison at Andersonville.

The bone-weary armies rested on the field until the night of July 4th, when Lee pulled his men out and headed South. As Meade followed Lee South in a pursuit which some deemed too slow, "the whole neighborhood in rear of the field" at Gettysburg became, an observer noted, "one vast hospital of miles in extent." Another man bringing medical supplies writes that "the process of cutting, carving, and butchering ... went on day after day." Such was the scene when Mrs. Elizabeth Donehoo, formerly Elizabeth McCreery, of Beaver, arrived in the little country town. She was the wife of Captain Henry Donehoo, 17th Pennsylvania Calvary, and heard the news of the battle, and that her husband had taken part in it. Failing to obtain permission in Harrisburg to visit the stricken field, she went anyway. Captain Donehoo, of course, was gone. He had done his fighting on July 1 with Anderson and McCabe and the rest of Buford's cavalry, and was now posting South with the army after Lee, as the war swung back into Virginia. But Elizabeth Donehoo found herself needed here in this town where the amputations continued day after day and doctors and nurses were too few for the task at hand. "She then devoted her time and attention in caring for the wounded, both Union and Confederate alike. From this time until the close of the war, she was prominently identified with the Christian Commission and was frequently in the front, engaged in caring for the sick and wounded."

The war would drag on for nearly two more years. There would be many battles. But of this particular battle Beaver Countians could echo the words of General Buford:

"A heavy task was before us; we were equal to it, and shall all remember with pride that at Gettysburg we did our country much service."