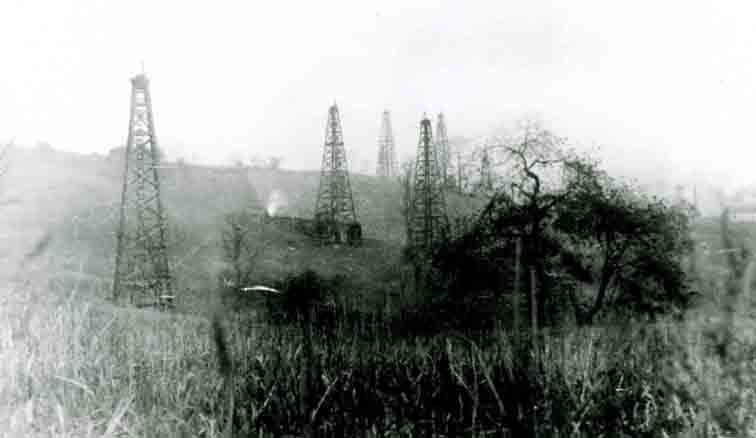

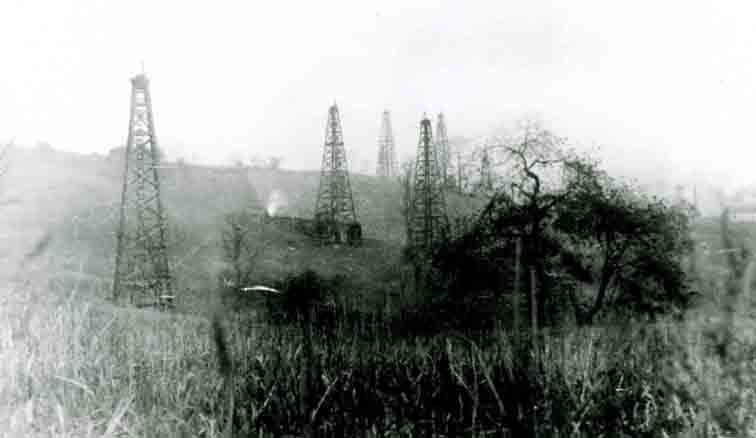

A view of some of the many derricks at Wallace City.

Click Here to Return to Milestones

"I see it is back on the New Sewickley

Township map," Irene Landis Slayton grinned concerning Wallace

City. The happy-go-lucky octogenarian promptly affixed, "I

guess they brought all the people back." She admits, "I

was just a kid and busy doing other things so I didn't pay much

attention." Her grandfather's farm, on a hill above Wallace

City, had 42 wells working at one time. "Oil," she went

on, "I do remember putting oil on my sister's hair. It made

it real dark and shiny."

Local Historian Don Musgrave's whose dad, Avery R., ran the Block

farm, laughed and added, "I'm afraid that a lot of us kids

were guilty of that." He explained that oil was good skin

lotion too. He praised its soothing liniment qualities also. "My

dad worked in oil most of his life and credited that for being

the main reason why he never got arthritis."

Wallace City is indeed on today's map, but it is official: The

only city in New Sewickley Township doesn't exist and is long

gone. It's a mere answer to a trivia question today--Just another

piece of history that's slowly becoming just that. It'll be recalled

as a lot of oil boomtowns were- a twinkle in this thing called

a universe.

A Venango County town, "Pithole," is no doubt the best

known in Pennsylvania to pull the disappearing act. The city was

born as the nation's Civil War was coming to an end, 1865. Within

in three months, it had some 20,000 people. Fred Sliter, museum

caretaker, honorary mayor, and author, said that "Pithole"

had its own newspaper, opera house, theaters, hotels, and of course,

soiled doves. Its post office during the final quarter of 1865,

ranked third in the state, handling 3,000 pieces of mail both

ways daily! However, 12 short years later, it was all over. In

1877, the parcel of land that was "Pithole", sold for

$4.37 - a far cry from the two million dollars that it sold for

in 1865. Today, the only proof of a town having been there is

a couple street signs. An informative museum is also on the site,

located on Rt.227 just a few miles east of Drake's Well and Titusville.

Soon after this field folded, many of the workers packed up and

came south to the action in Economy Township and New Sewickley

Township. Oh, the local community wasn't fancy enough to have

its own newspaper, opera house or theaters, but it did last longer

than its counterpart to the North. Its legacy goes on since it's

on the Economy Borough map too. Although a little weird, its lasting

quality can be seen by traveling west on the Turnpike and going

under Wallace City Road.

Here's hoping I do justice to a story of that city which refuses

to go quietly into the night. It had no intention on being here

one minute - gone the next. We'll start at the very beginning.

It wasn't the first oil field in Beaver County, nor the last.

The first hit was at Smith's Ferry in 1860 while "black gold"

was found at Glasgow in 1862. Then 1885, oil was discovered by

the Raccoon Oil Co. in Hopewell Township at a place called "Gringo."

This town was so named by an odd method. A local speakeasy reported,

"Men would get a drink, grin and go." So, they named

it "Gringo." This is probably the only town named after

a bar! In later years, 200 wells are under the waters of both

Kinzua Dam and Lake Arthur.

Economy Township, in 1800, was part of gigantic Sewickley Township.

In 1801, this big tract of land was divided into two townships,

North and New Sewickley. Economy Township was carved out of the

southern end of New Sewickley in 1827 and included Ambridge, Baden,

and Harmony Township.

The first community to break away was Harmony Township in 1851.

Baden followed suit and went on its own in 1868. Conway was the

next to merrily run along in 1903. Followed by Ambridge in 1905.

"Economy Township became a chartered borough in 1958,"

according to Musgrave.

"Frank Neeley was the first to strike oil in 1869,"

he added commenting that his farm was located in the Tevebaugh

Hollow behind Baden. From that point oil had a "domino effect"

on the area as farm after farm began drilling. The wells, about

1,300 to 1,400 feet deep, were drilled into what is called "hundred

foot" or mostly into an oil-bearing type of sand. Jim Floor,

of Ridge Road, noted that, "there are still some wells pumping

in that area today.

It wasn't long until oil was discovered on several other area

farms. By the turn of the century, the locality was being pounced

on by oilmen from other areas, including Franklin. Unpainted wooden

buildings quickly sprang up and the intersection of present day

Rt. 989 and Freedom-Crider Road became a beehive of activity.

Ms. Slayton's first cousin, Glenn Landis, said the town's main

and the most popular place was, "Jacob Bishop's packed General

Store." It sold about everything one would need then: chewing

tobacco, candy sticks, flour, pickles, pots, pans, and other foodstuff.

Also sold were work clothes, gloves, hats, shoes, and rugged boots

for those working in the fields. "Both my dad and uncle were

oilmen," Landis said in closing.

There were several blacksmith shops, a much-needed doctor's office,

several dwelling shacks and boarding houses. "We even had

a hotel up here," Economy's Musgrave said, indicating it

was up the road. An all important telegraph office was also in

town, and it'll be told later how critical that major communications

utility would become.

Folks in Wallace City could look out on the derricks built up

on all the once fertile fields. Oil was pumping at its fullest.

The sounds weren't cheery little songbirds or farm implements

clanging anymore, instead one could hear the echo of pipe hitting

pipe, gears meshing or the smudge-faced oilmen yelling back and

fourth.

The Robert Wallace farm, located on Dunlap Hill, was among those

that struck early. Thus it became probably the most prominent.

Therefore, the little town that mushroomed at the bottom of the

hill was dubbed "Wallace City." Virginia Roemoele, who

now resides near where that property was, points out that the

said land was where the first phase of Ryan Homes (Ridgewood Plan)

is now.

Ms. Juanita Reed, a former Economy Tax Collector, is a granddaughter

of Mr. and Mrs. Robert Wallace and grew up on that farm after

the untimely death of her parents. "I remember filling the

family car with it, right from the tap so to speak, and going

across the fields," she laughed. Ms. Reed is currently a

resident of the Chippewa Outlook Pointe Personal Care Home on

the Pappan business drive off old Rt. 51.

For a further understanding on how this worked, yours truly went

to a couple of experts: Bob Castelli and engine historian-television

personality Keith Blaho. Castelli, a high school friend and the

owner and operator of a small engine repair shop on Miller Road

near the New Sewickley municipal building said, "In those

days vehicles had multi-fuel engines. They were able to run on

anything that would burn." Blaho agreed. "But,"

he smiled, "It'd smoke like crazy." It was also pointed

out that some military vehicles are still powered by these "multi-fuel"

motors.

Farms of interest in Economy included; The Reed Homestead, Frank

Neeley's, Hagan's, Stewart's Farm, Smith's, Bradford's, the Whipple's,

Dunn's Farm, and Bock's property. Musgrave also started oil wells

on the Pfaff Farm which belonged to Henry Blank. This tract of

land is located behind the Grange Hall (now inactive) on Conway-

Wallrose Road.

Although it has nothing to do with the upcoming oil boom itself,

this writer was intrigued as to how "Wallrose" entered

the Economy vocabulary. According to the Historical Outline of

Economy Township booklet, a Henry Gross was the responsible party.

He broke away from the Harmony Society and opened a small store

on what was the Pittsburgh- Rochester Road. After a torrential

downpour, dirt began sliding by his store onto the road. He was

building a retaining wall when a neighbor praised it and suggested

he plant roses on it to keep it even more stable. Gross thought

a "wallrose" was a good idea and, a new word entered

the local glossary.

Fast forwarding a few years; many farms in New Sewickley Township

at this time were enjoying the oil boom. Most properties from

Pfaff's near Baden to Big Knob were erecting oilrigs, in hopes

of finding that brownish green or amber stuff. Before it was said

and done, the field was over six miles long and a good two miles

wide. Landis probably had the largest farm while others included:

the Morgan's, McElhany's and Kammer.

Musgrave cited that the South Penn Oil Company of Freedom held

most of the oil field holdings at that time. Quaker State also

owned some rights on the local market. South Penn, reportedly,

sold out to Ashland and was later bought out by Valvoline.

The Bock Farm had just been purchased by the Musgrave family around

1904. "You could say it was in transition," Don smiled.

But, he continued, it was written in the lease that the Bock family

received most of the proceeds.

Later the same year, on October 4, 1904, the 83 year young Musgrave

stated that they hit such a "gusher" that it took three

days to get under control. "Meanwhile that slimy crude splashed

down over the hill into the river." This is where the importance

of the telegraph at Wallace City shines through.

"They had to telegraph New Orleans to alert them and warn

all boats in the river of the big slick coming down." He

then put it into perspective, "It was putting out 85 barrels

an hour. There are 43 gallons to a barrel so over three days of

constant flow....." Whew, it's mind-boggling as to how large

it would be.

"Frank Neeley's Farm was directly down the hill from us.

He had just cleaned out his tanks, but our oil filled 'em, again

and again," the jovial Musgrave laughed. "Yep he got

lots of free oil-even being down!"

He stressed that this eruption shouldn't be confused by a Robert

Wallace well which put on it own show. It sprouted 1,400 barrels

a day and the geyser came out of nowhere. Thousands of kegs flowed

into Crow's Run before it could be stymied. Five hundred barrel

storage tanks were built to stop this one, and a three-inch line

was put down.

The peak came when the No.2 well on the Robert Wallace Farm hit

it big. The drilling around Wallace City would go on until 45,000

barrels a day was produced. The smaller Whipple Farm accounted

for 2,600 of those vats. Many of the wells dotting the Stewart

Farm turned out 250 kegs a day.

Although the Wallace Farm was the most notable, it was small and

had only 17 wells. The most one person had in Economy Township

was the Stewart's with 30. The Bock property had 19, the Whipple

Farm 17, and the Smith's had 10 or 12.

Even a church got into the act. The congregation of the United

Presbyterian Church (Rehoboth), which owed property boarding the

Robert Wallace Farm, made out a contract giving the Strohecker-Lamberton

firm of Zelienople, the right to bore for oil. It was agreed that

the church would be paid $200 for each 50-barrel well. The sum

of $1,000 would be paid to the church if a strike as good as the

No. 2 Wallace well was unearthed.

These monies would be besides the standard 1/8 land owner's royalty

for product sold. The church received a very small income as neither

of their wells brought much forth. Rehoboth has a very interesting

background. It was one of the areas oldest churches, organized

sometime between 1840 and 1850 as a Presbyterian Church.

The congregation, because of unrest, became inactive in the 1870's.

The now empty building was used as a sheep shelter for a number

of years. Finally, Dr. William A. Passavant and Dr. George Y.

Boal purchased it and, after a thorough cleaning, organized a

Lutheran congregation. A new church was dedicated on December

4, 1904, which served the congregation until 1967. "It's

a predominantly German neighborhood," Musgrave said. "We

figure 75% of those in Rehoboth cemetery are inter-related."

"Sinkholes are a big problem today," Marcia Scheel of

a Wallace City farm stated, "And figure this property had

42 wells on it." Her husband agrees, "And some still

oozing after all these years." Both explained that how the

oil wells were left caused havoc. "I'll bet that only half

are capped correctly." Marcia stated, "Sinkholes appear

overnight and we're afraid for the grandchildren," they echoed.

They are the current owners of what once was the Landis Farm.

"My son's house was here too," Fred said. "It was,

let's say, the "social club" with women and moonshine."

The rumor is that the "club" was owned by an unmarried

old man with no friends. "He didn't trust banks and so he

hid his money," Scheel smiled. Then with a more somber look,

he frowned, "I took out the walls and everything to remodel.

Even did some landscaping-but I never found anything."

"The region was also served by a train," railway expert

Wayne Cole volunteered. The author of several books on the mighty

vehicle, Cole continued, "It was owned by the North Shore

Railroad." About six miles long, it connected with the Pennsylvania

Railroad lines at the mouth of Crow's Run. It was put in early

to transport coal and oil field equipment. A turntable was installed

so it could turn toward the way it came from.

By 1902, it was necessary to extend the railroad further up Crow's

Run through a pair of tunnels. "This is where the train went,"

Ms. Slayton said, pointing to her garden. Train officials had

planned on cutting across Butler County to the Pittsburgh and

Western line at Callery Junction; that didn't happen.

But as that old saying goes, all good things must end. Drillers

began sinking hole after hole, only to strike-nothing! Panic set

in among investors and the city began fading into oblivion. Grass

could be seen sprouting again amidst some of the now idle wells.

The songbirds returned, and by 1937, all pipes were pulled. The

derricks were dismantled and the railroad tracks were torn up.

The two tunnels, off Park Quarry Road, have now almost totally

been reclaimed by nature.

Ms. Roemoele, who has been invaluable as to providing details,

maps, and tips, remarked that she still has evidence of the abrupt

ending. "I still have pipes rusting on my property."

When the oil stopped flowing, the men hurriedly pulled the pipes

out and "capped" the wells with whatever was available-a

stone, clay, dirt, or cement.

Things are pretty quiet now. Just a few wells continue to operate.

Most are in the Tevebaugh hollow woodlands. Musgrave said a man

named Anthony Cook owns those mineral rights in that area today.

"I understand he's a descendant of the family that Cook's

Forest is named for."

It seems the majority of seniors living in the Economy Township

and New Sewickley Township region, believes that "there is

still gold (the black kind, that is) in them thar hills."

Why the government isn't interested during this time of crisis

is beyond me. Or, is it a crisis? It's interesting to note that

both Lake Arthur and the Kinzua Dam, which each covers about 200

wells, were built in the mid 1960's--during the time Lyndon B.

Johnson, another Texas oilman, was president.

For our situation: Ms. Roemoele speaks out and says, "They

just got the easy oil." Son Randy agrees stating, "They

only skimmed the top." Musgrave shakes his head in the affirmative

and explains, "These wells yielded only about 20% of the

oil here. There's still 4/5's there."

Fred Scheel is in total agreement. "If we all had the mineral

rights and younger people knew what they were sitting on, we'd

all be in mansions." Flook nods his head, "It's been

a curse. When we had to drill our own water wells, we'd have to

go real deep or there would be slime on the water. Yes, there's

no doubt about it."

A mere handful of folks know the real story behind the city that

won't die. It was a time when the lush green fertile lands were

turned into a dust bowl in the summer and a mudstye in the winter.

For about 30 years, local farmers, instead of tilling the soil,

grabbed for that brass ring.

Today, there isn't much evidence that Wallace City ever existed:

some rusting pipe here and there, several places where one can

see salt water seeping above the ground, and those dangerous sinkholes.

Did it meet the criteria to be labeled a city in the modern world?

Hardly. But, it did for scores of people at one time.

However, dust to dust ........

Bibliography

Caldwell's Atlas: History of Beaver County

History of Beaver County 1904: Dr. Bausman

Pithole: The Vanished City: William C. Parrah

Rivers of Destiny: Many authors - A project of Beaver County Historical

Foundation

Other Publications

150th Anniversary of Economy Township: Barbara Kenny Fitzp

atrick and Michael Troyan

Dean's Column: C. S. Dean, News - Tribune Beaver Falls, Pa. Feb.

1952

Historically Yours: Gladys L. Hoover

Then and Now: Fred Sliter; D & S Printing Titusville - Fall

2006

Wallace City: A Boomtown Remembered: Rich Wasko, Beaver County

Times, Aug. 6, 1978