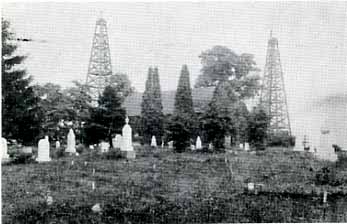

Two oil wells were drilled on the property of the Rehoboth Lutheran Church around 1901.

Return to Milestones Vol. 2, No.2

Norm Amsler is a Social Studies teacher in Beaver. He writes on the early oil industry with more authority than most: he spent many years helping his father in the oil fields. It's quite interesting to learn that the oil boom in Beaver County occurred only a year or so after the Titusville discovery.

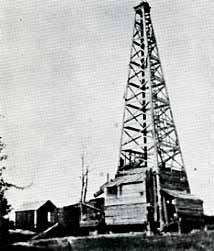

This title is a predictable reaction of many local residents whenever Beaver County's role in the petroleum industry is mentioned. However there was a time when wooden oil rigs towered over the landscape like giant sentinels waiting to reveal a hidden wonder of Creation and the pungent odors of crude oil and raw gas permeated the air like some strange, overpowering elixir. A few people can even remember the irregular but distinctive beat of a gas engine lifting drilling tools to the surface, the ring of a tool-dresser's sledge against a hot glowing drill bit, and the see-saw motion of a walking beam pumping an intermittent stream of oil from the 11 pay" into the receiving barrel, but for the most part these are sights and sounds that have all but vanished from the Beaver County scene.

Since this is the year for bicentennial reminiscing forget the problems of 1976 for the moment, and return with me to a more nostalgic era when oil production was one of the most important County industries.

The year is 1806 and the place is a spring located along the Ohio River on the opposite shore from Georgetown. Here an Englishman, Thomas Ashe, tested some oil oozing from the spring and found it comparable to the oil that Indians had been gathering for years along the shores of Seneca.Lake, N.Y. and Oil Creek, Pa. This was fifty three years before Col. Edwin Drake drilled his famous well along Oil Creek near Titusville, Pa.

About the same time that "oil fever" was rapidly spreading in Northwestern Pennsylvania after the Drake strike, some enterprising gentlemen, Messrs. Pattens, Finlens, and Swan, were busy drilling Beaver County's first oil well at Smith's Ferry in Ohio Township. The well was completed in December of 1860 at a depth of 180 feet. Although not an extensive producer itself, this well ushered in an era that would eventually turn our County into a "Boom town".

The next County oil strike of importance occurred March 19, 1862 when the Emeline Oil Co., composed of P. M. Wallover, 1. M. Pennoch, and F. Darlington brought in a well at the lower edge of Glasgow. This well was bottomed at 585 feet and produced oil up through the 1880's. With the completion of each successful well in the Smith's Ferry Field, oil speculation and excitement became more intense. During the period from 1860-1875 it was generally established that the Smith's Ferry oil reserves could be found 700-730 feet below feet below the Kittanning Coal or approximately 600 feet below the bed of the Ohio River. Although many wells were drilled in this area, none ever exceeded twenty five barrels per day until a fifty barrel well was completed in March of 1877 near Ohioville. One of the most shallow and short-lived wells drilled at Smith's Ferry was the "Good Intent" which was completed in February of 1891 by the Excelsior Co. It was completed at a depth of only 72 feet and the total production of this well was a mere 400 barrels before it was abandoned.

The years 1885 through the turn of the twentieth century saw oil speculators shift their attention up the Ohio River to other parts of the County. Since the principle oil strikes during this period occurred in Economy and New Sewickley Townships, I would like to share some of the more interesting facts of this oil field with you. Although I cannot establish a definite year, the older residents that I interviewed generally agreed that some of the first oil wells in Economy Township were drilled in Baden or Tevebaugh Hollow about 1895. The average depth of these wells was approximately 1200-1300 feet and were drilled into an oil bearing sand called the "hundred foot". Many of these early wells, some of which still exist, contained sufficient rock pressure to sustain free flow of oil without being pumped.

During the first decade of the twentieth century, more than one hundred wells were drilled in the Economy oil field on the Wallace, Reed, Stewart, Bock, and Whipple farms. This field, which stretched from the Big Knob in New Sewickley Township to the Pfaff farm in Economy Township, was approximately six miles long and two miles wide and during its peak years produced as much as 45,000 barrels of crude oil per day.

Most of the oil excitement in the above mentioned townships centered around a mini boom town called Wallace City. This village, which was located at the present intersection of Legislative Route 989 and the Freedom-Crider Road in New Sewickley Township, was so named for the Farm where many large producing wells were drilled. The No. 2 Wallace came in at over 1400 barrels a day and before it could be shut into a pipeline or tank flowed much of its production into Crows Run and then eventually into the Ohio River. It is interesting to note that in August of 1900, the Congregation of Rehoboth Lutheran Church, which owned land adjoining the Wallace Farm, signed an oil lease giving the Zelienople drilling firm of Strohecker and Lamberton -permission to drill for oil with the stipulation that $200.00 would be paid for each fifty barrel well and that $1,000.00 would be paid if a well as good as No. 2 Wallace was brought in. This money would be in addition to the standard one-eighth land owner's royalty for all oil sold. Two wells were drilled on the Church property but they were relatively small producers and netted the Church a very small income.

The oil speculation generated at Wallace City quickly spread to the neighboring farms of Stewart, Bock, and Whipple. The Stewart farm boasted thirty wells which ranged from 1000 to 250 barrels per day and the Bock lease included twenty one wells, the largest of which was the No. 2 Bock which was located in the field directly below the Economy Grange on Conway-Walrose Road.

The peak production of the Economy Field was reached about 1910. In that year the North Shore Railroad abandoned its spur line to Wallace City as an unprofitable venture because of the decline in oil speculation. Today Wallace City is only a memory in the minds of a few survivors of a generation that can still remember oil derricks dotting the hillside instead of the housing development that now appears there.

The discovery and production of crude oil in Beaver County spawned other local industries that included oil refineries and manufacturers of drilling equipment. In 1860 Samuel M. Kier of Pittsburgh began refining crude petroleum in Beaver County. By 1861 P. M. Wallover along with William Stewart, Milton Brown, and William

Dawson started an oil refinery at Smith's Ferry that still exists as the Wallover Oil Company. Another refinery, the Freedom Oil Works, now the Valvoline Oil Company, had its beginning in 1879 at Conway, Pa. with Stephen A. Craig and H. S. McConnel as its principle founders. A great portion of the Economy oil production was refined here because of its convenient location and accessibility to this oil field.

Other industries included manufacturers of drilling equipment - such as the Spang Chalfant Company of Ambridge, now Armco, that produced oil field casing, and the Keystone Driller Company formerly of Beaver Falls that made a port able steam drilling machine in 1882 that was more convenient to move and set up than the old standard wooden oil rig.

Besides new manufacturing many new occupations were developed as a cooperative part of the overall oil industry. Some of these occupations included: the pumper, who ran the machinery of the producing wells-, the gager, who measured and recorded the amount of oil in holding tanks before it was turned into pipe lines or hauled away; the teamster who hauled oil in tank wagons from wells inaccessible to pipe lines or railroads; and the contractor who repaired producing wells and "abandoned" those that were no longer profitable to operate.

Abandonment of an oil well was simply the reverse procedure of drilling a new one i.e. oil and gas bearing sands had to be sealed off or plugged with such materials as clay, stone, or cement; the strings of casing or pipe pulled out of the ground, and the surface equipment of engines, derricks, and tanks hauled away. The contractor who abandoned oil and gas wells had to know the approximate depth of the oil and gas sands of each well that he abandoned because inaccurate plugging of an oil or gas sand could result in salt water leakage into the sand and the eventual ruination of an entire oil field. The records kept by the driller of each wells depth of oil or gas sands was a great aid to abandonment contractor. My Father, who spent most of his adult life repairing and abandoning oil wells, sometimes would compare the abandonment of a well with a funeral. With a certain sadness in his voice, he would say, "Well, there is another one buried", as he pulled the last string of casing from the well and threw the last shovelful of dirt into the hole.

Most of these oil men, like the wells that they first created and then later abandoned, have faded into the background of County history and nostalgia, leaving us with only memories of a time when oil was more plentiful and life styles less hectic than they are today.

Thus our imaginary trip into Beaver County's oil heyday of the early twentieth century is ended and the stark realism of the oil shortages of today loom.. ominously before us as we celebrate our bicentennial year.