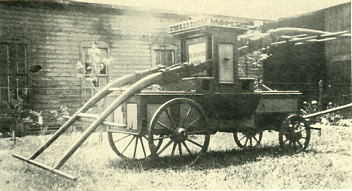

Economy's old fire wagon.

Click Here to Return to Milestones

The communitarian society had a very important place in the role of education in the United States. These societies, of which the Harmony Society was one, were the first to practice if not preach universal education, use kindergartens, nursery schools, universal secondary education, adult classes, and similar advanced notions. They were among the first to use a universal approach to supplementary education such as art classes and to emphasize the "practical" role of education versus the "classical". The reasons these other world societies were so interested in education are obscure. However, these societies were forced to find new solutions to old problems and education was one way of doing it. The Harmony Society stayed ever on the fringe of this "movement" but did participate in it to a certain extent.

There was a force tending to counter the need for education in some of these societies and that was fundamentalism. This force had been an important part of the Reformation and is still a factor in Christianity today. Fundamentalism takes on many meanings, but essentially it is a belief that every statement in the Bible is absolutely true. Although this is not important in itself, most fundamentalists believe that the only knowledge required is enough to read and understand the Bible. They are not against education - -just against too much education! The question is - - what is enough education? Fundamentalism worked against the tendency toward education, but in the broad pietistic movement these different ideas were constantly at war. The Amish believe that one can acquire enough education in four years and the Society of Friends believes in a universal education as high as one wishes to go. The Harmony Society was rather more fundamental than liberal, but they educated their members for this world as well as for the next.

The first evidence that the people who were to make up the Harmony Society had separated from the state church in Wurtemburg was when they withdrew their children from the church schools. The aims and methods of these schools were targets of the future Harmonists' distrust. They did not make quite so big an issue out of their other points of difference. They were baptized, married, and buried in the old Church, which was Lutheran. They even continued to attend services for awhile, but education was fundamental to their beliefs and they did not like what they saw in the church school. They conducted classes in their own homes. The quarrel was not with just the Lutheran Church - - they had Catholic and Reformed members who felt the same way.

One of the first things they did after they organized the Harmony Society in 1805 was to set up a school. Perhaps this met in the church building. The teacher was a remarkable man, Dr.Johann Christoph Muller, who had a university degree. He was a botanist and musician of sorts and the children must have received abetter education from him than the children usually had on the frontier. Also instrumental in education was Frederick Rapp, the lieutenant of George Rapp, the founder, and later (after 1826) Jacob Henrici.

Typical of most pietistic societies was the practice of dividing the group into "classes". These divisions were made on the basis of age, sex, and interest. The Harmony Society had such classes. We do not know much more about them but that they existed. Children under twelve, the young men, the young women, the older (say over 21) men, the older women, and each household made up the classes. Evidently these classes had study sessions in which they would take some problem and reach some sort of group agreement on it. The better of these "lessons" were read to the larger groups and the best were read at the church meeting and placed in the "Stuck" book. This book was in our possession until recently and would be very interesting to read, as it would indicate how the average Harmonist thought.

As the home was the basic unit in almost everything it was the basic unit in education as well. The constant discipline of the household molded the thinking and actions of the individual much better than any formal class could do. In many cases children, where there were any, followed their father's occupation, so that the lessons at the home were carried to their work.

Although the Society was celibate there were a number of children. These had a formal education in the school. They began school at about the age of eight. By this time they might have been taught their letters at home. The children attended the school from 8:00 until noon and had jobs in the afternoon. They attended six days a week and went all year. They were let out on the holidays and also let out to help with harvesting and other community tasks. They continued at the school until they were about twelve. At this age they were apprenticed to one of the craftsmen in the village or assigned some place they might learn a trade. At this stage they were considered to have advanced from the class of children to the class of young men or women. There would still be classes on Sunday and in the evening, especially on Wednesday, and occasional special classes during the day.

There were adult classes, too. The major emphasis in these, as might be expected, was religion. These classes were taught in the evening and on Sunday between church services. They also included a great deal of secular matter. Judging by the objects which remain, art, engineering, and mechanical thawing were the major subjects offered. The objects drawn in the art class were specimens in the museum, so these classes were also classes in natural history. Music was also taught and many travelers commented on the fine orchestra and chorus the Harmonists had. Judging by the few examples of art we have left there evidently were classes in penmanship which were advanced to the level of fractur, as we have many examples here. The village was designed by self-taught architects.

The Harmony Society was constantly buying school texts, partly for sale in the store but also for its own use. The first book printed on their press in 1824 was a songbook for the school. This was helped by the fact that the printer was Dr. Muller who also taught the school. One of the first books printed in Economy on the press was a spelling book for use in the schools. Their interest in both education and religion can be seen in that of the five books printed on the press two were for use in the school, two were hymnbooks, and the last (Thoughts on the Destiny of Man) was probably a sort of stuck book of George Rapp's thoughts. We have many examples of the exercise books from the later period of the Society and an example or two from the earliest period. Their education did not differ too much from that of the day; they emphasized rote memorization and recitation and stuck pretty much to fundamentals.

There was another side to the secular education. They had to educate a large number of people in a rapidly changing technology and supply themselves constantly with a new supply of craftsmen. The latter was supplied from the standard apprenticeship system already alluded to. Young men were evidently offered some choice in their occupation but not too much. Inside the Society there were several social layers and it was difficult for the son of a farmer, for example, to become a harness maker.

The Harmonists also occasionally apprenticed the sons of outsiders in their shops. These children were always ones who grew up in a family similar in views to those of the Harmony Society and had to speak German. After about 1820, when it became obvious that the Harmony Society had mastered the difficult skill of making yam and cloth with machinery many people tried to apprentice their sons to -the Society to learn this craft. The following excerpt of a letter is revealing about this activity:

.... It would have given me pleasure to comply with your request relative to your Son. But the fact that Scarcely any of the persons engaged in the Factory Speak the English Tongue, & the excessive Noise of the Machinery continually obstructing the hearing and comprehension of the Language which we are (not) even acquainted with, (would) but be a material drawback on a correct & easy acquirement of the Knowledge of each individual Branch of Manufacturing.

This was written in 1830 to a man in Wheeling. Notice that they would have expected to teach a number of different "branches" of manufacturing. However, they did take in apprentices from "outside", as in the case of Gottlieb Knapper, whom the Society took with them to Indiana in 1814. He was "bought" from his parents for $150, which is a reversal of the usual practice. George Rapp's portrait was painted by an apprentice cattle drover who would rather have been an artist (he did become one).

The Society had to learn the difficult techniques of setting up a woolen and cotton mill. There were no trade schools, technical literature, or industry-wide standards to make setting up machinery easy. They followed the machines and trained their workmen. There seems to have been a large body of men available. In the case of their steam engine in Indiana the engineer who set it up seems to have been a top expert and the Harmony Society formed a real liking for him. Occasionally the Society furnished technical training to outsiders, especially in the case of some of the fulling equipment they made and sold.

Learning English was a difficult job for those members of the Society who were allowed to live in the "world". They learned it by the method of thinking out what they wanted to say and translating. This is considered a very poor method today, but the doctor, Frederick Rapp, the Baker Brothers, and other agents seem to have done quite well. There is an undocumented story that Gertrude Rapp was sent to a Shaker community to learn English. We have an exercise book of hers in which she uses the method of writing out letters in German and translating them into English. One young man who worked in the store was refused the privilege of learning English and left the Society partly as a result of this. Evidently the teaching of English was used as a control of who would live in the world and who would not.

Living in and out of the world worked both ways. In 1828 Mary Ann Hay came to live with Gertrude Rapp at the Great House. Miss Hay was the daughter of the Harmony Society agent in Vincennes, Indiana. The things she was to learn with Gertrude (who was twenty in 1828) were instructive. She was to learn painting, sewing, knitting, piano, "and everything for female occupation". All correspondence with her was carried out in English, so Miss Hay probably did not know enough German to get along in the community.

This brings us to the education of young ladies after their schooling was finished. Most of them were given some occupation in the mills. A typical case would be a girl who would start out as a doffer in the spinning mill, work up to operating one of the spinning jennys, and when her training was complete be a full-fledged "operative" in the cotton mill and have her labor charged off at the fantastic salary of $2.50 a week. A few of the girls would become housekeepers, but most would acquire a skill and be more or less equal to the men. This was quite contrary to the American practice of the day and made staying in the Society quite attractive to its women members. A person who withdrew from the Society was much more likely to be a man than a woman for this reason.

Schooling was so important that only the leaders were allowed to instruct the young. George Rapp was first and foremost a teacher. Dr. Johann Christoph Muller (1788-ca. 1852) was a university graduate. He was one of Rapp's earliest supporters and one of the decision makers. He had charge of all of the intellectual activities, such as the school, choir, orchestra, botanical garden, and museum. He did illuminations, three of which survive. He was a doctor and druggist. Under the care of such a man we can hardly imagine that the students would not get an outstanding education. Dr. Muller was in charge of the school until 1832, so most of the people who were in the Society came under his tutelage.

Dr. Muller was also involved in the business end of the Society and was frequently sent on missions by them. If one had to rank Society members he would have been number three or four.

Jacob Henrici (1804-1892) joined the Society in 1826. After Dr. Muller left he became head of the school. He also had some university education. In his own way Jacob Henrici was as important to the Society's history as was George Rapp. He made the education a little more formal and divided it by subjects. As his duties as a head of the Society took more time the job of teaching was delegated. By the late 1850's the teacher had a minor role in the Society.

However, one must not forget that the first responsible job of John Duss, the last real leader of the Society, was that of teaching the school. If we wish to see the importance of education in the Harmony Society all we have to do is to look at who taught the school. Except for a period towards the end of the Society's life it was always one of the more important members.

There was an informal side to the education. The Society was rather intellectual and there were many educational advantages in the village. There was the large museum in the Feast Hall. This had art, scientific, and natural history objects. Next to this was the adult school. The Society had a zoo where native wild animals were kept, and a botanical garden. The garden was used to some advantage because one of the Society members, Hildegard Mutschler, who was trained in Harmony, Indiana, and Economy, impressed several visitors with her knowledge of botany. The intellectual discussions in the "classes", no matter how limited in scope, must have been very stimulating. The formal singing and music lessons must have had an effect also. The Harmony Society has often been painted as a group of narrow ignorant peasants but I would guess that many of them were quite intellectual. Narrow they might have been but I doubt that many were ignorant, save through choice.

I have hardly begun to touch on the education in the Harmony Society. They believed they were educating themselves for eternity and did a good job of it. On the surface they did not appear to have many chances at educational opportunities, but when we poke beneath the surface we see they had quite a few more than the typical American. Abraham Lincoln, growing up just a few miles from Harmony, Indiana, had practically no schooling at all.

Daniel B. Reibel