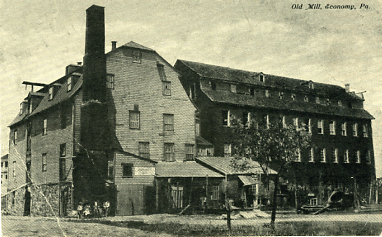

The steam powered grist mill(left) and the cotton factory(right.)

Return to Milestones Vol. 3, No. 4

In 1874, journalist Charles Nordhoff, studying the "Communistic Societies of the United States," visited Economy, home of the Harmony Society on the bank of the Ohio River in Beaver County.

"Neatness and a Sunday quiet are the prevailing characteristics of Economy," Nordhoff wrote. "Once it was a busy place, for it had cotton, silk, and woolen factories, a brewery, and other industries, but the most important of these have now ceased; and as you walk along the quiet, shady streets, you meet only occasionally some stout, little old man, in a short light-blue jacket and a tall and very broad-brimmed hat, looking amazingly like Hendrick Hudson's men in the play of Rip Van Winkle; or some comfortable-looking dame, in Norman cap and stuff gown; whose polite 'good-day' to you, in German or English, as it may happen, is not unmixed with surprise at sight of a strange face; for, as you will presently discover at the hotel, visitors are not nowadays frequent in Economy." .

As Nordhoff noted, "once it was a busy place." A booklet published during Merrick Art Gallery's Bicentennial "History Through Industry" exhibition declares that modern Beaver County "stands among the 10 leading counties in the Commonwealth and within the 50 leading counties in the nation in its industrial might." While Harmonist industries were not the first Beaver County industries by any means, they presaged modern Beaver County industries in their size and organization.

The members of the Harmony Society comprised a willing work force, bound together by common ties of nationality, language and religious belief. The Society's attorney, Richard P. Roberts, in 1855 referred to the group's "residence of nearly half a century in the Commonwealth, 'performing with alacrity its duties to the laws, rendering unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's,' " and to its "acts of benevolence and charity to the outer world, as well as ... the honest, virtuous and pious lives of its members." (Actually, the Society's residence in Pennsylvania had been interrupted by its sojourn from 1814-1825 in Indiana; and some charged that the "honest, virtuous and pious lives" of the individual members were too much under the control of the founder, "Father" George Rapp. But there can be no doubt that collectively these busy GermanAmericans exerted an influence far beyond their numbers.) They held their goods in common. Early during their residence in the United States they had adopted celibacy, a practice which, while it eventually doomed the group, during its heyday allowed the members more time for work without the distractions of child-rearing.

By the year 1825, when the Harmonists returned to Pennsylvania from Indiana to establish Economy in Beaver County, they had become expert in several areas of manufacturing. One witness in a lawsuit brought against the Society in the 1830's testified as to the Society's industrial holdings before the move to Economy. At the group's first settlement, Harmony in Butler County, this witness said, "there was a woollen factory, two grist mills, oil mill, saw mill, two distilleries, brewery, store and tavern; $50000 a year profit arising from the whole." At New Harmony, Indiana, this same witness said, "we had steam grist mill, woollen and cotton factories, oil mill, two saw mills, two distilleries, brewery, one store, tavern, grist mill. After paying all expenses, $50000 a year would not be too high an estimate of our profits." The reference to a steam grist mill is significant, for other testimony exists to show that by 1825 the Harmonists had learned to make the best possible use of steam. William Owen, inspecting the New Harmony settlement his father Robert Owen had purchased from Father Rapp, found "a cotton spinning establishment, driven by a horse and cow, walking on an inclined plane, a green for dyeing and bleaching, a dyeing house, a cotton and woolen mill, the former with power looms and the latter with a patent machine for cutting the nap. These are driven by a steam engine, which also sets an adjoining flour mill in operation.

By the summer of 1825 the Harmonists had transferred their industries to their new Economy settlement. Visitor Friedrich List wrote in his diary that "the factory" at Economy stood by the river, and that "two broad, beautiful paths lead down to the river, where a wharf is under construction for the sending and receiving of goods. Tailors shop, shoemaker's shop, cooper's shop, saddlery, wheelwright's shop, tannery, hatmaking establishment, apothecary and chemical laboratory, blacksmith shop, brickyard. A large threshing and blowing machine is being built."

By May, 1826, another visitor reported that the Harmonists had constructed "cotton and woollen manufactories, a brewery, distillery, and flour mill." All machines in these factories "were set in motion by a steam engine of 75 horse power and of high pressure, made in Pittsburgh"; the engine pumped "its own water from a depth of fifty some feet in a specially drilled well." All the factory rooms were "warmed during winter by means of pipes connected with the steam-engine."

Frederick Rapp, Father Rapp's adopted son and the efficient business manager of the Society, was not above a bit of quiet boasting about Harmonist industry. Noticing in an 1827 newspaper that employees of another cotton mill had turned out, during July, 1827, 11 at 12 hours per day," 4127 yards of sheeting, Frederick hurried with the paper to the Economy mill, and, according to his account, "communicated the same to our weavers. Three young Harmonist girls, he said, working 11 1/2 hours per day for a month, managed to produce 5201 yards. "It is really a great pleasure," Frederick concluded, "to notice the rapid progress the American nation has made in so short a time in the various branches of manufactures."

The value of Harmonist wool products rose from $35,681 in 1827 to $84,571 in 1831. Somewhat after this peak period, the Society, under the direction of Father Rapp's granddaughter Gertrude, began silk manufacture as well. And once again they entered into this new venture in a big way. By 1836, they had set out 10,000 white mulberry trees, fed 500,000 worms , and produced 96 pounds of silk. But by this time, their larger manufactures had begun to fall off. A great many of the younger workers had left with Count DeLeon in 1832. On November 25, 1833, the Economy woolen mill burned to the ground. While it was rebuilt, it never regained the productivity of the halcyon years. And the Society lost its business genius with the death of Frederick Rapp in 1834. Aaron Williams commented in his 1866 history of the Harmony Society that "it is not to be wondered at that in such a community, where no provision is made for its perpetuation, where the young are growing old, and the old passing away, there should be a gradual decadence in taste and enterprise. The cotton, woolen, and silk manufactures were abandoned years ago--the last because it was not profitable, and all, because there was a lack of mechanical skill in those whose eyes needed the aid of glasses and whose hands were becoming tremulous."

Harmonist money, generously applied, maintained the industries of others for years after their own enterprises had come to an end. (As a result of one such investment, Harmonist Trustee Jacob Henrici was for a time President of the Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad.) And, when at last the Society collapsed, much of the Harmonist land was sold to the American Bridge Company, which gave its name to the new town, Ambridge. The industries are different, but, once again, the site of the old Harmonist settlement is "a busyplace. "