Aliquippa's J&L Steel Mill

Click Here to Return to Milestones

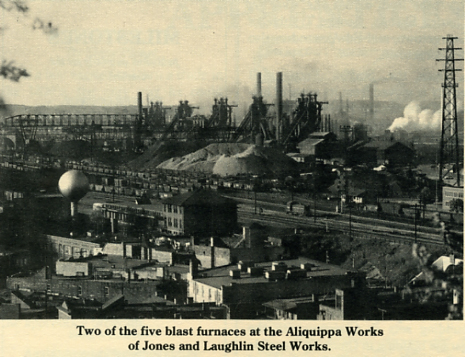

While many people have a vague understanding that the steelworkers of western Pennsylvania contributed to the advancement of organized labor in the United States, most do not realize the extent of this local effort. It was not by accident that the Steel Workers Organizing Committee, an off-shoot of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the forerunner of the United Steelworkers of America, was originally formed and headquartered in Pittsburgh. Nor was it incidental that the first test of the SWOC's strength happened at Jones and Laughlin's Aliquippa Works.

The history of the organized labor movement in America is a confusing jumble of strikes and lockouts, contracts signed and broken, which begins in the mid-nineteenth century and continues today. The current, bitter strike at Wheeling-Pittsburgh Steel, and the rhetoric surrounding it, mirrors dozens of other similar incidents dating back more than 100 years. The charges of unfair union demands and unethical management practices have echoed for as long as "Big Steel" has existed.

While there was some initial acceptance of unions in the industry in the mid-1800s, the infamous Homestead steel strike of 1892 quickly and surely ended any good feelings between unions and management. That strike, by the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel, and Tin Workers against the Carnegie Steel Company, and its bloody results, not only set a tone of loathing between the two sides, but kept the western Pennsylvania steel industry virtually unionfree for over forty years.

Anti-union tactics were enacted in a variety of ways, some of them obvious and some of them more insidious. The management of Jones and Laughlin's Aliquippa plant seemed to deal in both methods. According to David Brody in his book "Labor in Crisis", Aliquippa was one of a handful of steel towns in which union organizers risked their well being merely by entering the city limits. According to Brody, Tom Girdler, the superintendent of J&L in Aliquippa in 1919 and later the head of Republic Steel, arranged a welcome party for organizers as they entered town. In one such incident, as soon as the organizer got off the train in Aliquippa, two men began to shadow his every move. It was only a few hours before the union man got the hint and headed out of town.

One of the more covert ways in which J&L tried to control their workers was by keeping them segregated, at work and at home. Migrating steel workers had caused the population of Aliquippa to swell from 3,140 to 15,426 between 1910 and 1920 and the new residents were hardly a homogenous group. Forty percent of them were foreign born and a large percentage of the remaining population was black. But rather than allowing these diverse groups to blend, J&L deliberately kept them apart. According to Dennis Dickerson's book, "Out of the Crucible most of the laborers in the South coke works, the by-product coke works, and the 14 inch rolling mill (three of the least desirable locations in the entire Aliquippa Works) were black. In addition, all 1500 black employees at J&L mills were working at unskilled labor.

Dickerson notes that ethnic and racial groups were kept separate at home also. Shortly after the Aliquippa Works was built in 1906, J&L started the Woodlawn Land Company which helped shape Aliquippa (and the borough of Woodlawn which merged with Aliquippa in December, 1927) as a mill town. Woodlawn Land Company, AL's real estate branch, built the Franklin Avenue commercial district, several public buildings, and many residential neighborhoods for their workers. But it was part of the company's policy that workers of differing racial and ethnic groups be pushed into geographically separate neighborhoods. One example cited by Dickerson is Plan Eleven Extension, built in the 1920s by J&L to house only black workers.

The most logical motive that J&L management could have had for preventing Aliquippa's new residents from intermingling was to maintain a higher level of control over them. By keeping a physical division between blacks, Hungarians, Italians, and Slovaks, management kept a psychological division as well. The strength of unions is, as the very name indicates, in joining groups of workers for a common cause. If J&L kept each group distinct on the job and in the home, they would lessen the chances of them banding together.

In place of unions, in the 1920s, J&L had adopted a policy called the Employee Representation Plan. The ERP had the look of a union, with employee-elected representatives who negotiated with management, but it had little real power. In 1936, when ERP members of AL's Aliquippa and Pittsburgh works wanted to be recognized as a single unit, their request was flatly denied by management. This led to five of the ERP leaders publicly resigning and joining the newly-formed Steel Workers Organizing Committee.

The book "United Steelworkers of America", by Vincent Sweeney, states that the first ever meeting of the SWOC was on June 17,1936 in downtown Pittsburgh. Philip Murray was chairman of the meeting (this date is still celebrated as Phil Murray Day), and representatives of various other trade unions filled out the group. Sweeney says that among the committee's stated goals was to "avoid industrial strife and the calling of strikes, if we are met in a reasonable spirit by the employers, and to concentrate all our efforts on recruiting members into the Amalgamated Association of Iron, Steel and Tin Workers."

Within a year, the SWOC had gained the kind of national momentum that no steel union had previously. On March 2,1937, the SWOC signed a contract with steel titan US Steel, with the meeting once again taking place in Pittsburgh, this time in secret. The results of the contract though, were national news - $5/day minimum pay and a forty hour work week, with time and a half overtime. The contract also set paid holidays and addressed health and safety issues at the plants.

Once monstrous US Steel had recognized the SWOC, it became obvious to smaller companies that the new union would have to be dealt with, and many of them hurried to sign SWOC contracts to keep labor peace. Sweeney states that by early May, 1937, 110 firms had come to labor terms with the SWOC. But one notable exception was J&L

As noted in the examples above, J&L was known for its hard line stance against unions, and the SWOC, in spite of its burgeoning strength, was no exception. Negotiations between J&L and the SWOC were at an impasse, and the union decided to test the resolve of its new members. On the night of May 12, 1937, picket lines sprung up at J&L's Aliquippa and Pittsburgh Works, and the strike was on.

Approximately 25,000 workers from the two plants walked out in the first major strike in the SWOC's history. And, in spite of its historic connotations, it also turned out to be one of the shortest. Within 36 hours, J&L's management agreed to a vote by its employees on whether to accept the SWOC, and vowed to sign a contract if the new union won. When the election was held on May 20, J&L workers voted more than two to one to accept the SWOC. The new union had flexed its muscles for the first time and won.

The 1937 strike hardly signaled the beginning of good management union relations. On the contrary, some of the strikes that followed were among the fiercest and bloodiest ever. But the test of unity that the workers at the Aliquippa Works passed in May, 1936, in spite of years of social planning to the contrary by J&I, became the first benchmark by which the SWOC, and later the USWA. would be measured.

Reference:

"United Steelworkers of America, Twenty Years Later, " by Vincent Sweeney, published by VSWA 1956.

"Out of the Crucible. Black Steelworkers in Western Pennsylvania in 1875-1980", by Dennis Dickerson, State University of New York Press, 1986.

"Labor in Crisis: The Steel Strike of 1919" by

David Brody, J R Lippincott Co., Philadelphia, 1965.