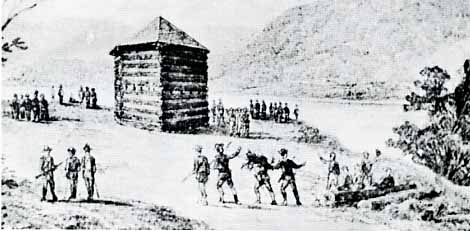

An artists conception of the Big Beaver Blockhouse (from Bausman.)

Click Here to Return To Milestones Vol 6 No 2

In 1788 the National Government decided to abandon Fort McIntosh in favor of a newer type of fortification and one more strategically located. A War Department order, dated October 2, 1788, read:

This blockhouse, built by Colonel Josiah Harmar with troops from Fort McIntosh, was located on the present site of New Brighton. It stood on what is now the west side of Third Avenue below Fourteenth Street. The blockhouse was never given a formal name. Although the small stream cutting through the southern end of the town gets its name from this fortification, at no place is it nearer than a quarter mile from the site of the building. Troops were kept here as late as 1793, as the blockhouse was the most advanced position held by the United States against the Indians in the Ohio country at this time. Though one writer of the period describes it as only a large hut, the log fort must have been of fair size as the muster roll of 1792 shows a garrison of 19 soldiers. During its occupancy, several soldiers died and were buried in the blockhouse graveyard which was located on the west side of Third Avenue, just south of Fallston Alley. It was during this period that the blockhouse was the keypoint of a tragic event in local history. A distinguished ex-Revolutionary officer friend of George Washington, author, and one of the prominent men of the nation, together with a companion was drowned at the middle falls on November 17, 1789.

The man was Major General Samuel H. Parsons of Connecticut, ancestor of the distinguished Parsons and Lathrop families of New York state, one of whom was the writer, George Parsons Lathrop. The name of General Parson's companion was Captain Joseph Rogers. Little is known of him except that at the time of the accident he had been referred to as "the man with a broken leg."

Early in November, 1789, General Parsons and some companions left the blockhouse, then in command of Lieutenant Nathan McDowell, to proceed on horses to finish a survey of lands known as the Western Reserve at Lake Erie. They journeyed as far as Salt Springs on the Mahoning, about 45 miles distance, in which Parsons was financially interested. His indisposition and a sudden change in the weather stayed further progress, and he decided to return.

Turning about and being accompanied by Captain Rogers and another man, he retraced his way as far as Old Moravia, where the General and the man with the broken leg, determined to descend as far as the blockhouse by water. Leaving the third man with instructions to bring down the horses. Parsons remarked that 'he intended to dine that day with Lieutenant McDowell at the blockhouse.

Notwithstanding the fact that the Beaver was very high, the General and his companion embarked in a canoe; and that was the last ever seen of them alive. The weather grew very cold and a severe snow fell. As the man with the horses traveled southward, at several places where the trail neared the river, he saw tracks in the snow where someone had landed from a canoe and warmed his toes by kicking his boots against a rock, and then more tracks back to the canoe again.

He did not get to the blockhouse until evening. Parsons and Jacobs were not there. He learned, however, that about noon a partly smashed and upturned canoe, a pair of saddle bags, and some other articles had floated past the fortification. The soldier occupants were unable to retrieve anything except some other minor paraphernalia from the flooded waters. The horseman, however, immediately identified these as the property of General Parsons.

A search was started forthwith for his body, but the river promptly froze over; it was not until after the spring thaws, or upon May 16, 1790, that the remains were found by William Wilson, the trader, near the mouth of the Beaver. The general was buried in the vicinity of the blockhouse, but history is silent as to the recovery of Captain Jacob's body. [Captain Rogers??--Ed.]

It is not surprising then that we find a record of a trading post existing almost as soon as the blockhouse at the foot of the Falls. The Beaver and its tributary, the Mahoning, constituted part of the water highway leading from the Great Lakes to the settlements. The hides of furbearing animals of the latter region were transported by the Indians in canoes up the Cuyahoga River as far as the depth of water would permit, and then portaged to the headwaters of the Beaver or its tributaries, whence they were soon brought down to where white men were waiting with powder, lead, firearms, and strong liquors for exchange.

At this same trading post a tragedy occurred which not only stirred up the decent people upon the frontier, but reached the War Department and resulted in an order by General Knox, Secretary of War, that Col. Samuel Brady, the noted Indian fighter, be arrested and tried for murder.

The winter of 1790-1791 was one of comparative quiet on the frontier, though a few depredations were committed south of the Ohio River. No means existed to prevent small parties of young savages from crossing that stream between the mouths of the Beaver and Yellow Creeks, stealing horses from the settlers, carrying off plunder, and committing an occasional murder.

In early March, 1791, Captain Brady with about 30 followers set out in pursuit of such a raiding party, but failing to overtake the savages, came to the bank of the Beaver opposite the blockhouse. Observing a party of nine Indians bartering at William Wilson's trading post across the stream. Brady and his men secreted themselves in a swampy alder thicket which formerly existed near the present west end of the Fallston bridge, and opened fire upon the savages. Three men and one woman were killed, and the remainder fled, whereupon the Rangers crossed and secured nine horses, all arms of the Indians, and the goods they had purchased. A boy took refuge in the house of the trader who protected him.

The deed was promptly denounced a,s deliberate, atrocious murder by the best people of the frontier, for it appears in letters of General Pressly Neville, Major Isaac Craig, and others, found in the Pennsylvania Archives condemning the outrage that some of the Indians were Christian Moravians. Some were known to several of Brady's men and called out to them loudly in English when the firing began.

Moreover, the red men had with them their squaws, their horses and the young boy, together with articles of trade. The experienced frontiersmen well knew that this would not be so if the savages had hostile intentions. All fair minded people on the western border realized that such treatment of the Indians was a grievous mistake, and steps were taken to bring the guilty party to account. However, the courts on the frontier moved just about as slowly then as they do today, and it was not until May 20, 1793, that Colonel Samuel Brady was arraigned for the murder in the Criminal Court at Pittsburgh. No denial was made of the killing, but the perjured testimony of Giasuta, a noted old Indian, astonished Brady's own lawyer with his versatile imagination which he explained later by stating that he was a friend of Brady. According to the old reprobate, the party of savages at the trading post had about the worst reputations possible, and whether they had ever been guilty of any atrocities or not, they were bad enough to have committed them anyway; etc. The learned judge gave the jury no chance. He said that in his opinion the defendant was not guilty; and if the jury agreed with him, he would discharge Brady. What else could a jury do? So the prisoner was found not guilty, but directed to pay the costs. This is probably the first time such a verdict was rendered relative to Beaver County offenders, though similar findings have continued to puzzle citizens ever since.

The vicious killing of friendly Indians when they had been trading at a store, as Major Craig termed it, had an immediate two-fold effect. It roused the savages to a frenzy of increased raids upon the settlers, with the usual murders and scalpings; and the border population was seized with such terror at the promptness and savagery of the Indian's reprisal, that upon the 31st of the same month Colonel Wilkins wrote from Pittsburgh, that for an extent of fifty miles the people of the frontier had fled, abandoning their farms, their stock, and their furniture.

In the following three months, fourteen persons were killed, wounded or carried off in Allegheny County alone. Henceforth there was no cessation of savage warfare on the western border, until President Washington selected Anthony Wayne to lead a fourth expedition against the Indians beyond our northwestern frontier.

Wayne arrived in Pittsburgh, in June 1792, and within two months secured the necessary 2,000 recruits for his command. He organized his men under the name "The Legion of the United States." During the month of November, in order to be closer to the scene of hostilities, Wayne moved to a position twenty-two miles west of Pittsburgh on the right bank of the Ohio. This station was appropriately named Legionville. It was located west of the present town of Ambridge where the old redoubt can still be faintly traced among the myrtle and ivy. According to Wayne's diary, the discipline in this camp was very rigid. Camp followers were quickly dispersed and the use of whiskey was strictly prohibited which was a new regulation for the American Service. It was while here that the men learned the art of marksmanship and the tactics of Indian warfare. While here too, Wayne acknowledged the receipt of certain battle flags and standards from the War Department adding in his brusque fashion, "They shall not be lost." So by the time that the winter was over, the Legion had developed into a real organization, with a soul and a feeling of esprit de corps, unknown heretofore in the military expeditions against the Indians.

So thorough and intensive had been the training Wayne gave his Legion and so high the state of discipline, that the Indians of the northwest realized they were not going to fight against weak and unprepared troops as had been true on previous occasions. Consequently, they retired to a point near Detroit where behind a carefully constructed breast-works, they took up a strong defensive position. Here Wayne met them with his 2,000 men, and although greatly outnumbered, captured their breastworks with the bayonet and after the killing of great numbers forced the survivors to surrender. It was in the battle of Fallen Timbers fought in 1794 that the Indian power of the Old Northwest was forever broken, and the Treaty of Greenville signed the following year which established a lasting peace between the whites and the natives in this region.

Surely we can well feel proud of this great achievement when we recall that the force employed by Wayne was largely recruited from this region and trained for this exploit, within the limits of Beaver County.

The establishment of permanent peace between

the races brought an era of prosperity to this region. Settlers

poured into the country beyond the Alleghenies. Many chose the

Valley of the Beaver as the site of their future homes. Forests

bordering the river were rapidly cut down, and the cleared land

turned into farms. Out of this wave of settlement, villages rapidly

sprang up; and the Beaver Valley frontier passed into history.