Click Here to Return To Milestones Vol 8 No 1

Several articles have been written in past years about the operation of the Patterson Heights "incline". Some of the information and accounts in those articles will be repeated in this writing, but as one whose home was adjacent to the site of the car barn at the top of the hill, I would like to share some of my fond memories of its history and operation.

The Patterson Heights Street Railway was capitalized for $6000.00 in 1895. This was actually four years before Patterson Heights was incorporated as a borough (1899), having been part of Patterson Township or "Riverview" prior to that time.

The Patterson Heights Street Railway, better known as the "incline" was built by John Reeves, an early resident, who, it has been said, received inspiration for its operation through observation of mining equipment during travels in the western part of the United States.

The total length of the car line was approximately three-eights (3/8) of a mile. Commencing at the bottom terminal, located at the foot of Bridge Street, where it joins what is now Seventh Avenue extension, Beaver Falls, the line proceeded in a north-westerly direction along the curb line of Bridge Street to the bottom of Ross Hill at the current site of the Independent Banker Computer Service, Inc. At this point, it crossed Bridge Street and proceeded in a westerly direction between Ross Hill and the now abandoned Patterson Heights or Country Club Hill for a combined distance of approximately one eighth (1/8) of a mile to a position at the bottom of the straightway in roughly a north-south line to Patterson Heights. To this point, the car operated in the same manner as any other street car. In order to traverse the inclined straightway, however, it required a cable assist, which will be described later. The straightway portion was approximately one-quarter (1/4) of a mile long with a grade of approximately 20 percent or twenty-feet to the hundred.

In the construction of the straightway section of the incline, two major cuts were made on the west side of the right-of-way. Philip (Phil) Erath, Jr., one of the better known operators, had stated that these cuts were hand dug - steam shovels not being in common use at the time.

The cabled portion of the incline was unique. It consisted of the one track the length of the hill or incline for the passenger car and an adjacent track for the counterweight car, more popularly known as the "dummy", which travelled only the upper half of the incline. The "dummy" car, weighted with scrap iron, weighed slightly less than the passenger car.

The cable arrangement, which permitted the movement of the passenger car and the dummy in a two-for-one travel distance, was accomplished through the use of horizontally mounted pulleys or sheaves. One pulley was mounted at the top, a second beneath the track bed at the bottom of the incline and a third mounted in the dummy itself. The anchor points for the cable ends were at the top and half-way down the incline at the end of the dummy track. In order to "climb" (the expression used in that day) the hill, the operator would grasp the stationary cable with an apparatus on the car known as the "clutch" or "grip". After grasping the cable, the car would proceed up the hill. Two, fifty-horsepower motors, which powered the car itself from a conventional overhead trolley wire, also moved the cable. As the car started its climb, the dummy car at the top, resting on a short level spot, proceeded off that spot and down the track. When the dummy started down the grade, only nominal power from the car motors were required to take the passenger car up the hill. The dummy, by the same token, acted as a brake on the return trip down the hill.

In approximately thirty years of operation, no major accidents occurred to the car, although on one or two occasions, the dummy "got away" (as was the expression), when the cable was not properly "gripped" as the car proceeded up the hill.

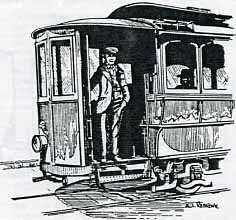

The passenger car was not too unlike the popular conception of the "Toonerville Trolley". The windowed passenger compartment consisted of carpeted bench seats positioned on either side of the length of the car and could accommodate approximately ten to twelve adult passengers. The fact that the seats were carpeted reduced the possibility of the passengers sliding to the lower end of the car as it made its way up the hill. Not taking any chances in our young lives, however, my brothers and I generally tried to get seats at the upper end of the car. Normally, however, we would sit on a covered box containing sand for the track in the forward, separate, operator compartment going up the hill. Sand was used occasionally when the tracks were wet or icy.

The passenger car required a cable assist as described, but on at least one occasion, as related by Phil Erath, the car was able to make it to the top without a cable and only sand on the track. Needless to say, there were no passengers and the track was dry.

Seven operators reportedly served the incline during the course of its history. These men, in addition to Phil Erath, included George D. Hill, George Erwin, Fred Harn, John Wittenberg, George Wenkhouse and Homer Barrett. The incline operated from early morning until late in the evening on two shifts with one operator each shift.

The top and bottom terminals of the incline were equipped with waiting rooms for passengers. The top terminal was a large black corrugated metal building which also accommodated the passenger car and contained a pit for making repairs and performing maintenance on the underside of the car. The bottom terminal was a small building probably no larger than eight feet by eight feet square. The terminals were equipped with hand-cranked bells which signaled the operator on the other end that a passenger or passengers were waiting. It took about ten minutes for the passenger car to make the trip. Trips were not made on a regular schedule, but rather as required to accomodate the greatest number of passengers. Waiting time, in any case, would normally not exceed twenty minutes and would probably average between ten and fifteen minutes. I still recall George Erwin moving the car one length out of the car barn and peering up Spring Street (now Sixth Street) Patterson Heights for possible late passengers before making the trip down the hill.

My brothers and I shared a bedroom on the

west end of the house nearest to the car barn. We recall vividly

that during the dark evening hours, the lights from the car window,

as it traveled down the hill, would race across the ceiling of

our bedroom, accompanied by the familiar sound of its motors.

Long after it ceased operation, the sound of the motors remained

with us unaccompanied by the moving car lights.

The history of the incline is not without some amusing stories. It was fairly common for school boys, attending downtown schools in grades seven through high school, to hitch a ride up the hill without the assumed knowledge of the operator. On one such occasion, a student thought he had successfully eluded detection. He was much surprised the next day, however, when the operator stopped by his house on his way to work to claim the six cent fare. Crime, as always, did not pay!

The passing of the incline was due, for the most part, to three factors. First, and foremost, the automobile was gaining in popularity and the need for commercial transportation was beginning to decline; second, the need to raise the fare from six cents to a dime, in order to offset decreasing ridership and increasing costs and third, the change in the traffic pattern when a new railroad bridge was constructed and street cars and other vehicular and pedestrian traffic was re-routed over the reconverted railroad bridge, which now is, itself, slated to be replaced. In addition, the main Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad Station in Beaver Falls, was moved at the same time from its location across the street from the bottom incline terminal to a new location opposite the ramp to the new traffic bridge. Prior to these events in 1925-1926, the incline was convenient to street car and train travellers.

1927 was the last year of the incline's operation. It had served its purpose and the time of its passing had arrived. Modes of transportation keep changing and it is noteworthy that the year of its passing was the same year that Charles Lindbergh conquered the Atlantic in the "Spirit of St. Louis", which was to usher in yet another means of commercial transportation.