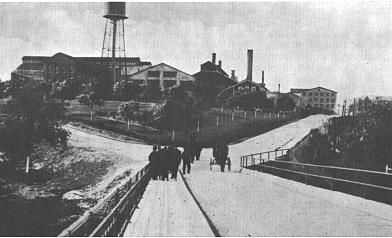

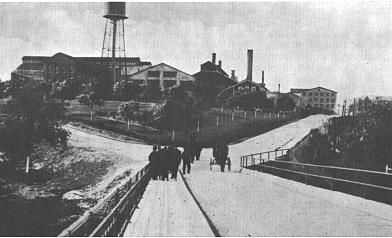

The Fry Glass Works in North Rochester in its prime.

Return to Milestones Vol. 5, No.2

At one time, the tri-state area was known as the "frontier line" of the Midwestern glass industry, due both to industrial boundaries of the U.S. and the importance of the area in the glassware industry.1 Factories were located along riverways in Pittsburgh, Steubenville, Beaver Valley, and into West Virginia. The Fry Glass Co. of Rochester, Pa., with its quality glassware and international trade, was one of the most respected plants. 2

Henry C. Fry, the founder of the company and a sharp businessman, was involved in the glassware industry from the age of sixteen, when he was a shipping clerk for the William Phillips Glass Co. of Pittsburgh, Pa.3 His father, Thomas, was linked with the Curling, Robinson and Co. Glass House of Pittsburgh, Pa.

In 1862 Henry left the Phillips Co. to enlist as a private in the Penna. Cavalry, 15th Regiment. In 1864 he left the cavalry and became part of the management of the Lippencott, Fry, and Co. glass house.4. In the Spring of 1872 Mr. Fry left the Lippencott Co. in order to manage a new glasshouse, The Rochester Tumbler Co. This company, located on the bank of the Ohio River close to rail lines, was noted for advancements that it made in glass production. It was the first glass manufacturer to foresee the value of using natural gas for heating operations as well as being one of the first companies to specialize in the manufacture of one item, tumblers.5 Mr. Fry had a gas well drilled on his property that supplied fuel for the furnaces, illumination inside the plant, and oil at the rate of two barrels a day.6

On February 12, 1901, the world renowned Rochester Tumbler Co. was destroyed by fire. Mr. Fry had earlier seen his company plagued by floods because of its proximity to the river and so decided to rebuild on a high spot. He purchased twelve acres of land in North Rochester and began construction of the Fry Glass Company.

The H. C. Fry Glass Company was organized with $400,000 capital and the aid of the Rochester Business Men's Association.7 The Association, organized on March 30, 1901, provided capital for the construction of a railway line to the new Fry plant -- a line needed for supplying products to Fry's trade centers.8 On June 28, 1902, with rail lines finished, the H. C. Fry Glass Co. opened for business. The company had a patented glass-making process, five hundred employees, and acquisition of the Beaver Valley Glass Co. across the street. The Beaver Valley factory was used for the production of everyday ovenware.9 The three hundred glassware patterns that had been used at the Rochester Tumbler plant were still manufactured but a new and exciting pattern was developed by discoveries in the new plant.

There were several factors involved in the discovery of the new pattern including a lawsuit filed against the Fry co. by the Pyrex Glassware Co.10 The Pyrex suit contended that Fry's production of transparent ovenware was infringing on the established market that Pyrex had for its own transparent ovenware. As a result of the suit, the Fry Co. began experimenting with alterations of its ovenware pattern.

Workers in the Fry plant had already been discovering that the quality and color of their glassware were being intensified by the higher flow of air and gases in their new smokestacks.11 The high elevation of the smokestacks, above the tree tops, gave more life to the furnace fires and resulted in unusual distribution of color in the glassware. The unusual color distribution aided in the birth of Fry Pearl Oven Glass. Further development of the mixture used for glass production resulted in the most beautiful of all Fry products - FOVAL.

FOVAL stood for Fry Ovenglass Art Line and artistic it was. The pieces of FOVAL produced ranged from baking dishes, to coffee pots, to personal sized tea services. They started with a deep shade of blue, jade green, or rose at their bases with the tint lightening to smoky shades as it reached delicate edges.

The mixtures used for glassware production were jealously guarded secrets.12. The Fry mixture was extravagantly high in lead content with only the finest quartz used.13. The quality of the white sand and Missouri clay used for the furnace pots were equally important.

Fry glassware was produced by talented glassblowers or from molds. One of the most famous glassblowers employed by H. C. Fry was Peter Gentille. Mr. Gentille emigrated to the United States from Naples, Italy, at the age of twenty-seven with many years of glassblowing experience under his belt. While employed at the Fry plant, Mr. Gentille and a co-worker known as "Frenchie" invented the "Old Glory Paperweight", one of the most famous of paperweights.14

While Fry molds were patented, they were not used exclusively by the Fry Co. Some molds were used to produce "Blanks" (undecorated glass) which were sold to smaller companies, like DeVilbiss Perfume Co. of Toledo, Ohio, who found it less expensive to buy blanks than to produce their own.15.

Mr. Toni Santelli who worked in the Fry finishing room related to me in an interview that it was a common practice among glasshouses to hire quality workers from competitors, thus insuring a high quality product.

The market for Fry products extended throughout the United States, to Great Britain, Germany, Belgium, South America, Canada, and even parts of Africa.

The local economy was very dependent on the Fry Co. with five to six hundred laborers being employed during peak business times. The employees included men and women who worked in shifts and were paid an average wage of $4.00 for an eight hour day.16. After finishing their shift, the workers were permitted to make their own pieces of glassware.17 The workers had high regard for Mr. Fry and the plant foremen: Mr. Betts, Mr. Bloom, and Mr. White; as well as for each other. Mr. Fry had earned a reputation for disliking unions and there was never a union at the Fry plant.18

When the plant went into receivership for the second time, in 1933, employees were paid back wages in glassware. At the time, this method of payment probably seemed of little value to employees who had families to feed. However, today those pieces still in existence are worth a great deal of money.

The Fry Co. had skilled craftsmen, willing laborers, envied recipes, good furnaces, facilities for making shipping containers, ownership of a natural gas company (The Beaver, Butler Gas Co.) a water refining plant on company property, membership in the National Glass Co. cartel (Henry Fry was a founder and President), and patterns of rare beauty. How could the company have fallen apart? Its first receivership occurred in 1926 for reasons of bankruptcy. It had its problems during the "crash" of 1929. In 1931, Mr. Henry Fry died and his eldest son took over, but was unable to maintain the company's profits. In 1933, the company went into receivership for the second time and the Libbey Company acquired the buildings. They maintained production for approximately three years and then folded. The Beaver Valley works was sold to a private concern. Many of the Fry molds were sold to the Phoenix Glass Co. in Monaca, while others were destroyed to become part of a steep bank behind the plant. By 1940, the buildings were standing in ruins with the famous smokestacks crumbling. The remains of the twenty pot furnaces deteriorated and became part of the basement and ground beneath them.

All that remains of this once great business are many treasured collector's pieces of Fry glassware and the mystery of how such a promising industry could have failed and disappeared from the Beaver Valley.

1. Mr. Elmer Rex, interview, April 14, 1979.

2. Lowell Innes, Pittsburgh Glass 1797-1905 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.), p. 60.

3. Book of Biographies of Leading Citizens of Beaver County, Pa. (New York: Biographical Publishing Co.), p. 201.

4. Ibid.

5. Innes, p. 45.

6. Ibid.

7. Rev. Joseph H. Bausman, History of Beaver County, Penna. Vol. 2. (Buffalo: Knickerbocker Press), p. 742.

8. Ibid.

9. James R. Lafferty Sr., Pearl Art Glass-Foval. (by Lafferty) p. 3.

10. Rex, interview.

11. Dorothy Daniel, Cut and Engraved Glass 1772-1905.(New York: M. Barrows and Co.), p. 176.

12. Lafferty, p. 7.

13. Daniel, p. 176.

14. Lafferty, p. 11.

15. Jean S. Melvin, American Glass Paperweights and Their Makers. (New York: Thomas Nelson and Sons), p. 53.

16. Toni Santelli, interview, April 1, 4979.

17. Lafferty, p 8.

18. Innes, p. 57

Bausman, Rev. Joseph H. History of Beaver County, Penna. Vol. 2. Buffalo: Knickerbocker Press, 1904, pp. 741-742.

Book of Biographies of Leading Citizens of Beaver County, Pa. New York: Biographical Publishing Co., 1899, pp. 201-203.

Daniel, Dorothy. Cut and Engraved Glass 1771-1905. New York: M. Barrows and Co. Inc., 1950.

Innes, Lowell. Pittsburgh Glass 1797-1905. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1976.

Lafferty, James R. Sr. Pearl Art Glass--Foval. pub. by Lafferty, 1967.

Melvin, Jean S. American Glass Paperweights and Their Makers. New York: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1967., pp. 53-67.

William Baker, interview on April 21, 1979.

Myrtle McCready, interview on April 3, 1979.

Elmer Rex, interview on April 14, 1979.

Toni Santelli, interview on April 1, 1979.