Click Here to Return to Milestones

Walking around Oak Grove Cemetery in Freedom,

one is astounded by the number of monuments that have been erected

in remembrance of so many loved ones. We need only to pause and

read the gravestones as we get to know a little about each person;

when they were born and when they died, and in some cases, who

they married and who their children were. Every gravestone gently

reminds us of our shared destiny and offers the hope that we will

not lie forgotten as though we had never lived. Yet, amongst these

silent sentinels, there lies a man whose only memory consists

of a simple numbered marker that lacks even his name. A man who

once lived, loved, struggled and suffered as we do, but who now

lies lost and forgotten to all but the most curious visitor. His

name was Jonah Key and this is his story.

Jonah Key was born in Frederick County,

Maryland in March of 1838. We know very little about his early

life, but most likely he was born into slavery and freed at some

point. In his later pension records, Key indicates that he did

not know his parents, strongly suggesting that he was either orphaned

at an early age or that they or he were sold. Some rumors also

link him as a slave to Francis Scott Key at his estate Terra Rubra,

which is not far from Union Bridge where Jonah settled for a time.

Another interesting fact is that Jonah's last name was "Key"

and it was standard practice for a slave to take the surname of

his master. At present, research can neither prove nor disprove

this idea. Whatever the truth may be, we do know that in the 1850

census he is listed as a "free inhabitant" and is living

with a man named William Haines in Johnsville, Maryland for whom

he worked as a 12 year old laborer. Also listed on the census

with him was an 11 year old girl named Susannah Key who was possibly

a younger sister.

The next glimpse we have of Key is in the

1860 census, at age 21, where he is living with a blacksmith named

Moses Jones in Union Bridge, Maryland and is apparently learning

the trade from him. In 1861, as the nation was sliding inexorably

toward Civil War, Jonah Key married Virginia Dick who gave him

his first child, son John A. Key. We can only assume that the

couple was happy during those early years watching their son grow

as they worked together to build a better life together. But future

events were to change all of that forever.

On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln

put into effect his Emancipation Proclamation which freed the

slaves that were being held in bondage in any state or designated

part of a state which was in rebellion against the United States.

The problem with this was that the Emancipation Proclamation did

not free slaves in any states such as Maryland which were still

a part of the Union. However, for free men of color like Jonah

Key, the most powerful effect of this extraordinary document was

to allow the enlistment of black men into the Union army.

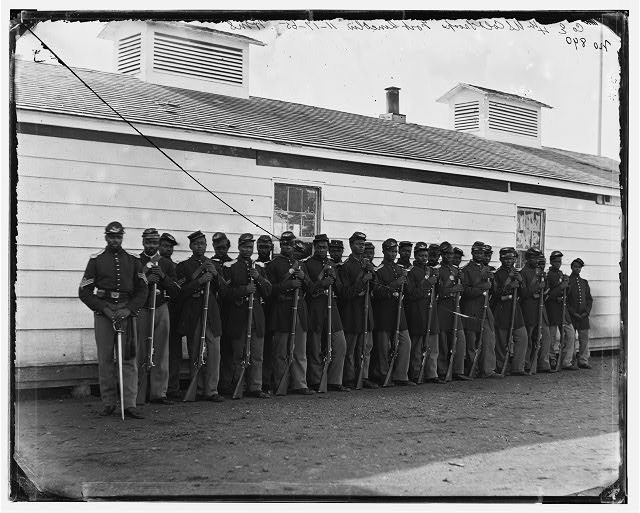

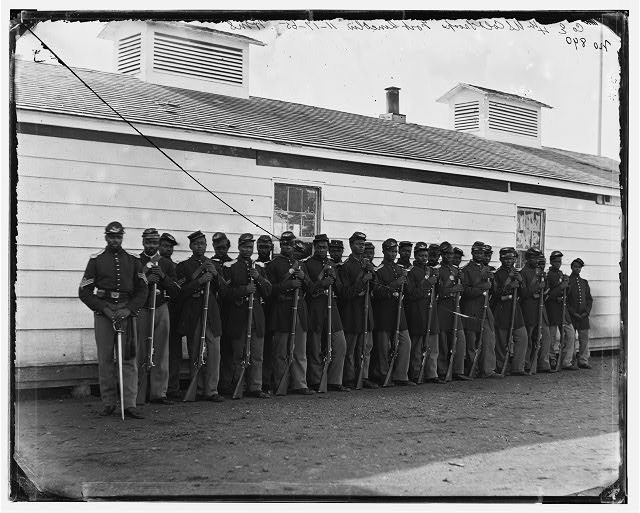

On August 4, 1863, Jonah Key left his family

behind as he traveled to Baltimore and was officially enlisted

in Company F of the 4th United States Colored Troops being formed

there under the direction of Colonel William Birney. At this point

in the war, colored troops, as they were called, were still considered

inferior by many northern white officers and consequently, were

poorly equipped and used mostly to do the manual labor required

by any army such as digging fortifications, offloading supplies

and other non-combat tasks. Another problem facing black troops

was the discrepancy in the rate of pay that they were given versus

that given to white troops.

Black troops faced other more dangerous

types of discrimination when they were finally sent into battle.

There were several incidents during the war in which surrendering

black troops were murdered by Confederate troops. Probably the

most notable occurrence was when Confederate cavalry general Nathan

Bedford Forrest captured Fort Pillow, Tennessee in April, 1864.

The small earthen fort was defended by a mixed garrison of both

white and black troops when Forrest attacked with over 2,500 Confederate

cavalry. When the Fort finally surrendered, Forrest was accused

of allowing his men to massacre many of the black soldiers since

only 62 of the original 262 were taken prisoner.

Fate was not much kinder to those black

soldiers who were taken prisoner as there was always the danger

of being returned to slavery. One report from the 44th United

States Colored Troop, came from a soldier who had been among the

350 black soldiers captured and sent to a Confederate prison camp

in Mississippi. According to his account, almost 250 black soldiers

were returned to their former masters, or those who claimed to

have owned them, thereby returning these men to slavery. Yet despite

these problems, black men continued to join the northern armies

and contribute to the cause of freedom.

After learning their rudimentary drill at

Camp Birney in Baltimore, Jonah Key and the 4th U.S.C.T. were

shipped to Fort Monroe in Virginia. Now under the command of Colonel

Samuel A. Duncan, the 4th was thoroughly trained as a fighting

unit and sent on to Yorktown, Virginia and the unit was assigned

its first combat mission. In early October of 1863, along with

several white units, the 4th took part in an expedition to sweep

the countryside of Confederates soldiers and sympathizers. Despite

a lot of marching, not much combat action was seen, but the Union

force destroyed over 150 boats and captured a group of uniformed

rebel regulars, guerrillas, and suspected sympathizers. Brigadier

Isaac J. Wistar, commander of the expedition, in a letter to Colonel

Southard Hoffman on October 9, 1863, had the following to say

about the performance of the 4th U.S.C.T. : "The Negro infantry

marched better than any old troops that I ever saw. On two days

they marched 30 miles a day without a straggler or a complaint,

and were ready for picket, patrol, or detachment duty at night.

Not a fence rail was burned or a chicken stolen by them. They

seem to be well controlled and their discipline, obedience, and

cheerfulness, for new troops, is surprising and has dispelled

many of my prejudices."

Following this successful action, Jonah Key was promoted to the rank of corporal as the 4th settled into a very comfortable routine of garrison duty at Yorktown until the spring of 1864 when they were assigned to the Army of the James under the command of General Benjamin Butler. Under Butler, the regiment served with distinction at the battles of Bermuda Hundred, Fort Converse, and the first and second battles of Petersburg. It was during this last mentioned battle that Jonah Key received the wound that would end his military career and cripple him for life.

On June 15, 1864 the 4th U.S.C.T. was assigned

to a force commanded by veteran General William F. "Baldy"

Smith to launch an attack against the important railroad supply

junction of Petersburg which was the key to the eventual capture

of the Confederate capitol of Richmond and the destruction of

Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. In the early morning

hours of June 15th, Smith was pushing his force closer towards

Petersburg when suddenly they began receiving heavy cannon fire

from the crest of a steep slope to their front. The 4th was ordered

into a battle line along with the rest of their brigade which

had the unenviable task of assaulting the enemy position. The

avenue of attack was a tactical nightmare that required them to

advance through a dense wood almost 600 yards deep which opened

to marshy ground covered with fallen trees, high bushes and all

manner of other natural obstacles. Each trooper would have to

cover another 300 yards of this killing ground while under heavy

fire from both cannon and small arms.

Amidst the roar of Confederate cannon, the

attack order was given and the battle lines surged forward into

the heavy woods. In short order, the units became tangled with

each other and some lost their way completely, but the men kept

moving forward. Seeing what was happening, the brigade commander

ordered all units to halt at the far edge of the forest and regroup

before continuing across the open ground. In their excitement,

three companies of the 4th did not hear the order to halt, burst

out of the trees screaming like madmen and charged across the

open ground by themselves. The target was too easy for the eager

Confederate gunners and their supporting infantry as they concentrated

their murderous fire against the small Union force. In a short

time over 120 men were killed or wounded. Meanwhile the rest of

the brigade, having reformed, charged the rebel works and captured

them. Throughout the day, the 4th and her sister regiments were

instrumental in capturing several more heavily defended positions

that would eventually open the way to Petersburg. It was sometime

during this action that Corporal Jonah Key was hit by a musket

ball that traveled through his left wrist near the joint and exited

through the back of his hand.

Following his wounding, Key was treated

and eventually taken to the Grant General Hospital at Willet's

Point, New York. The doctors there determined that the Minnie

ball had fractured all of the bones in the wrist and hand causing

the hand to form into a hook shape with the thumb contracted into

his palm. He was not able to move either fingers or thumb again,

and the disability was total and permanent. Jonah Key's war was

over.

On April 1st, 1865 following almost nine

months of treatment at Willet's Point, he was discharged from

service and returned home to his family at Union Bridge, Maryland

with a disability pension of $4 per month. From this point forward,

Jonah had a great deal of trouble finding work, due to his disability,

to support his growing family as second son, William F. Key had

arrived in 1863.

Sometime during 1869, the Key family left

their roots and moved north to Allegheny County, Pennsylvania

to find work. The 1870 census lists him as a laborer and the 1880

census lists him as a carriage driver in Bellevue along with his

wife and sons.

On December 27, 1892, Jonah's wife, Virginia passed away and was

buried in nearby Uniondale Cemetery in Allegheny County. Key lived

on and continued his home in Bellevue on his recently increased

$40 per month pension. During this time, he met and fell in love

with Harriet Warfield Snowden, a recently divorced woman nearly

20 years his junior, and on April 15, 1905 they were united in

marriage by the Reverend Polk Knox Fonville. They remained living

in Bellevue for many years until Jonah fell ill in late 1919 or

early 1920. Harriet tried to take care of her husband, but doctors

determined that Jonah needed more care than she could give, and

sent him off to the Disabled Veteran's Home in Dayton, Ohio. This

was to be the last time that Harriet saw her husband alive. Late

in the evening of April 12, 1920, Jonah died of heart failure.

In the meantime, Harriet's own health had suffered, and she moved

to New Brighton to live with her daughter. There another tragedy

unfolded as her granddaughter, Thelma Flood also passed away within

days of Jonah. His body was sent back, and he and his granddaughter

were given a double funeral service at the A.M.E. Church and interred

at Oak Grove Cemetery in Freedom. There Jonah found his final

resting place while his widow fought the government for both his

pension and a marker for his grave. Almost a year after his death,

in a May 26, 1921 letter to the pension bureau, Harriet says:

"I also would like to know why they have not placed no tombstone on my husbandes (sic) grave. He has been dead a year or more and he is a honorable discharged soldier and there is not even a mark on his grave and I hope you will look it that he get a tombstone or the Bureau for the state."

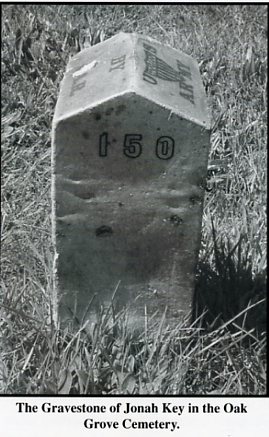

Although Harriet finally got her pension, Jonah's grave never received a gravestone; the only indication that anyone is even buried there is the plain G.A.R. (Grand Army of the Republic) marker #150. Beneath this simple marker lies the body of a soldier who once gave his hand in the cause of freedom, who toiled throughout his life with this extra disability, and who has been all but forgotten in death. As historians. it is our sacred duty to blow ever gently across the gradually dying embers of remembrance in a hopeless attempt to slow the ever encroaching darkness of ignorance and neglect. A small flame now flickers for Jonah Key.