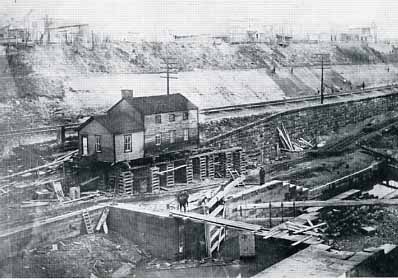

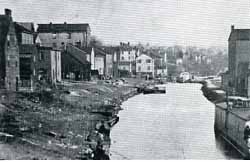

At Girard Lock in Rochester, the locktender's house is moved to make way for the railroad. This 1905 view shows the lock four years after it was abandoned.

Return to Milestones Vol. 5, No. 4

"I got an old mule and her name is Sal, Fifteen miles on the ERIE Canal. "

The Erie Canal was the longest and most traveled of all of the 19th Century towpath canals. Most of us remember the Erie Canal song from school, but how much did we learn about canals in history class? The fact is that the early 19th Century canals did much to tame and settle the western frontier - a generation before the railroads came. The history books, though, seem to give the railroads all the credit.

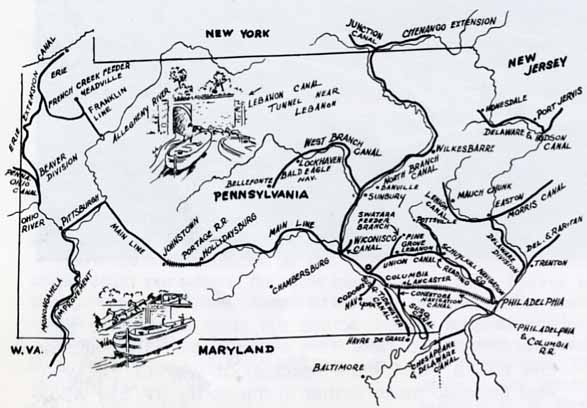

The digging of a canal from the Hudson River to Lake Erie across 400 miles of wilderness was a crazy idea. With difficulty, Dewitt Clinton and a few others managed to persuade the New York State legislature to authorize what would become one of the greatest engineering projects of all time. Despite many vocal critics, the canal was built. This waterway was in operation only a few years when its fabulous success fostered imitation and competition. After watching traffic in New York harbor increase tremendously at the expense of their own ports, the neighboring seaboard states of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia hurried into construction of their own east-west canals. At the same time, the inland states of Ohio and Indiana were eager to build north-south canals to haul away the massive flow of freight and immigrants being carried to Lake Erie by the Erie Canal.

"She's a good old worker and a good old pal Fifteen miles on the Erie Canal."

The mule was the motive power on the canal just like the diesel tractor is on today's highways. Treat her well [keep her well lubricated-with oats] and she'll work hard for you. The mules were driven along the towpath, and the canal boats were towed along behind. Two teams of mules working alternately and changed every four hours or so, could haul a boat up to 40 miles a day at two to three miles an hour.

Pennsylvania was certain that her "Main Line" canal and railroad system across the state would take business away from New York's Erie Canal. After all, the Erie was a much more roundabout way to the west. And being so much farther to the north, the Erie would freeze earlier in the Fall, and thaw--several weeks-later in the Spring! But Pennsylvania--and Maryland, and Virginia--underestimated one little problem that New York never had to cope with: the Appalachian Mountains.

Maryland's Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (projected initially from Baltimore to Pittsburgh) ended at Cumberland, her plans to tunnel under the Alleghenies and reach the Youghiogheny River never realized. The James River and Kanawha Canal, working west from Richmond, Virginia, managed to breach the Blue Ridge, only to be forever stalled in the foothills of the Alleghenies.

"We've hauled some barges in our day, Filled with lumber, coal and hay."

There was more coal hauled than anything else on the towpath canals, especially on the Eastern Pennsylvania canals and the C & 0. But statistics don't do justice to the fact that with the canals, the farmer in western Pennsylvania or Ohio could now ship his corn and wheat back to eastern markets--at a nice profit--and in return, receive goods that would raise his standard of living considerably. Iron stoves, china dishes, window glass--these were all but unknown in the west before the canal. No longer would such merchandise need to be hauled over the Alleghenies on the painfully slow and terribly expensive "Pennsylvania wagons", pulled by six horses over occasionally non-existent roads.

Pennsylvania would overcome the mountains, not by waterway but by a clever system of ten inclined planes connected by level railways. The "Main Line Canal" followed the Juniata westward from the Susquehanna above Harrisburg. At Hollidaysburg, boats (especially designed for the system) were hauled out of the water and placed--in three or four sections--on flat rail carriages. These cars were towed by horses to the foot of the mountain to plane number ten. (There is a village there today called "Foot-of-ten.") They were then hauled by a steamdriven cable up the slope (on an "inclined plane") to the next level. This was repeated four more times before the crest of the mountain was reached. Then the cars, with their marine cargo, would descend the mountain via another series of five planes and an equal number of "levels". Eventually, the cars reached the basin at Johnstown on the Conemaugh River, which, most importantly, was a tributary of the Ohio!

The Allegheny Portage Railroad, as the entire system was called, scored two important engineering firsts: one is the Staple Bend Tunnel, on level number one east of Johnstown, which was the first railroad tunnel in America. And a young engineer named John Roebling, challenged by frequent (and tragic!) accidents on the steep planes due to failure of the hemp cables, developed the first wire rope cables. Immediately successful, wire rope would later be used by Roebling on the Brooklyn Bridge and by countless other engineers on the major bridges of the world.

The canal followed the Conemaugh, Kiskiminetas, and Allegheny Rivers to Pittsburgh, there meeting the navigable Ohio River and thus helping Pittsburgh to maintain its calling as "Gateway to the West".

The Erie Canal paid back its construction costs through tolls in only seven years of operation, then repeated this feat many times over the years, None of the other major canal systems were to break even financially. This is not to say that the Pennsylvania Canal was not successful--the settlers at the far end of the canal benefitted immensely--and so did the Philadelphia merchants.

"And we know every inch of the way, From Albany to Buffalo."

It is no coincidence that a band of large cities stretches across central New York like pearls on a necklace. The Erie Canal was called the "mother of cities" and among her progeny are Schenectady, Utica, Rome, Syracuse, Rochester, and Buffalo. Freight from the Erie would transform distant villages into Cleveland, Toledo, Cincinnati, and Erie, Pennsylvania.

Even the legendary success of the Erie Canal was not enough to convince the entire Pennsylvania legislature that a canal/railroad system across the center of the state would solve all its problems. No, a compromise was required, and this was largely in the form of branch canals. The city of Erie fought for, and eventually received, a branch canal leading north from Pittsburgh. This canal, when finally constructed, followed the Beaver and Shenango valleys north to the summit at Pymatuning, then Conneaut Creek down to the lake plain. A branch from Conneaut Lake was built to Meadville and Franklin, but traffic never developed along this route. Instead, the branch fed water from the French Creek into the Beaver and Erie Canal.

The Canal in Beaver County was built in stages. First, the Beaver Division was built (1832-1834) from Rochester to "Western Reserve Harbor" (now Harbor Bridge village, above New Castle.) Then the "Erie Extension Canal" was projected, with the Shenango Line extending north to the summit, and the Conneaut Line completing the route to Erie. The uncompleted extension, however, was sold by the state to a private company and opened, finally, in 1844.

"Low bridge, everybody down

Low bridge, for we're coming to a town."

Bridges over the canal were built no higher than necessary to clear an empty packet boat - and anyone sitting on top of the cabin would likely be knocked off. The term "low-bridge" later came to mean a severe blow received unexpectedly. In a sense, Pennsylvania had been low-bridged by the lack of windfall revenue from her canal system, but, at the same time, canals everywhere were suffering the first sljns of "railroad shock," a trauma with which at least some of them would learn to cope but none would fully recover.

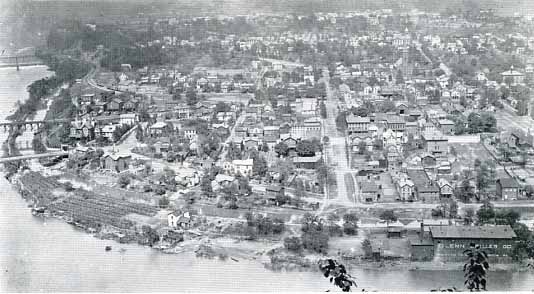

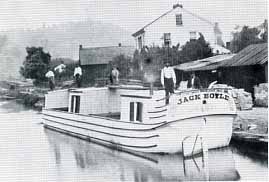

The Beaver and Erie Canal would birth her cities too; Bridgewater, Rochester, New Brighton, New Castle, Sharon and Greenville were canal towns, though all but the first would eventually thrive on manufacturing when the canal was gone. The canal began at Rochester with two oversized locks named for Philadelphia philanthropist Stephen Girard. A dam at the locks created a pool above it which permitted boats to float across to Bridgewater warehouses. In time, however, Rochester succeeded her neighbor as the leading canal port. Some canal boats were towed down the Ohio from Pittsburgh to enter the Beaver and Erie, but much more freight was unloaded from steamboats that plied the Ohio and then transferred to waiting canal boats for the trip north.

Boats passing the Girard Lock were towed through the slackwater pool to New Brighton, where a flight of four locks lifted the canal around the lower falls of the Beaver. The river wall of the first of these locks (the Blount Lock) is visible today from the Fallston Bridge. The other three locks (Boyle's, Buck Woods' and Van Lear's locks) were covered by the Pennsylvania Railroad in its 1926 relocation from 5th Avenue, New Brighton.

Yet another lock, (the Dutchman's lock) was located at the upper end of New Brighton, opposite Beaver Falls, and adjacent to the dam under the Tenth Street Bridge. Beaver Falls was known as Brighton during most of the canal period. Brighton village represented an early attempt to capitalize on the considerable water power available from the Beaver River. The effort had failed, though, and the town was eclipsed by her neighbor and progeny, New Brighton, to the south. The town was sparked to life again in 1868 with capital from the Harmony Society. Reborn as Beaver Falls, the new town soon watched its canal die, but it had the railroad (two through lines by 1878) and it had water power. The Harmonists' Beaver Falls would soon be an industrial giant, unmatched in Beaver County until the steel era began in 1905.

The Eastvale Dam now supplies drinking water to much of the Beaver Valley, but it was first built as a canal dam. Just below it, two locks, Bannon's and Farrow's locks, lifted canal boats to the slackwater pool above the dam. This was called the Seven-Mile Level, for there were no more locks until Rock Point, at the mouth of the Connoquenessing Creek near the present county line. Part of Farrow's Lock remains on the river bank below the dam.

"Oh, you'll always know your neighbor,

You'll always know your pal,

If you ever navigated on the Erie Canal."

There was a camaraderie among canallers, just as there would be among railroaders and as exists among truckers today. Only the Girard Locks were officially named,- the others received their names for canal boat captains or hands who had distinguished themselves at that location. This was usually in the form of a successful fist fight, to determine whose boat would enter the lock first. Society barely tolerated canallers on the waterfront and not at a# elsewhere. Farmers quickly learned that their crops, chickens, and daughters were never safe from the marauding boatmen.

When the canal was built, Beaver County extended north to meet Mercer County at the village of New Castle on the Shenango River. Within 15 years, New Castle had become a major canal port with enough political clout to have her own county formed, over the objection of her neighbors who would be forced to contribute the land. Between Rock Point and New Castle were seven more locks, all but the last built in Beaver County.

Before we leave Rock Point, however, we should touch on the Beaver and Erie Canal's special legend: James Garfield, who would be president of the United States, was a mule driver on the canal. One night, while crossing the mouth of Connoquenessing Creek in slackwater, he fell overboard and would have drowned but for a rope trailing in the water. This he quickly grasped, and was able to pull himself to safety. He was put up for the night in the Matheny tavern nearby. This canalside inn, built in 1836, was a century old when it was demolished. When canal days ended, it served as a station on the New Brighton and New Castle railroad. The stone foundation is easily located. A short stretch of canal is also visible at Rock Point, but nothing remains of the lock.

At Mahoningtown, near New Castle, the canal branched. The original ditch followed the Shenango north, but another canal was built along the Mahoning and crossed the Shenango on an aqueduct to join the main route. The new canal was called the Pennsylvania and Ohio Canal by officials of each state, but it was the "Crosscut Canal" to everyone else. Built in 1837, the Crosscut Canal soon captured the major share of traffic from the Beaver Division and carried it westward to Youngstown, Warren, and the Ohio and Erie Canal at Akron.

It is said that the canals died of an overdose of steam. It is true that they would have been around much longer if the railroads hadn't come in so soon. But when they came, the railroads could haul freight a little cheaper and a lot faster. So, one by one, the canals were abandoned, dried up, or were covered by railroad tracks. It appears that the railroads are following the same path today.

Before we follow the canals to their unhappy extinction, we must look at another Beaver County waterway. The advantages of a link between the Beaver and Erie and the parallel Ohio and Erie Canal (Cleveland to Portsmouth, OH) were not overlooked by the citizens of New Lisbon, Ohio, nor the farmers of Columbiana County. In an extraordinary effort, enough cash was raised by local subscription and from merchants in Philadelphia to build the Sandy and Beaver Canal. This worthy effort amounted to too little and too late, and lost three million dollars for its supporters. Completed in 1848, the Sandy and Beaver operated for only two or three summers over its entire length. It left a priceless collection ' of lock remains in the valley of the Little Beaver, including Lock 54, which is in Beaver County, just inside the state line. The canal terminated with Lock 57 at the village of Glasgow, which is Beaver County's other canal town. A branch canal was projected to link the S & B with the Beaver Division along the north shore of the Ohio; it never happened.

Most of America's canals weren't even wet yet when the Baltimore and Ohio's steam engine proved its worth by outrunning a horsecar. The word quickly spread, and a network of tracks was soon to follow. Iron rails reached Pittsburgh in 1851, and the same year in the form of the Ohio and Pennsylvania Railroad, the hissing, snorting, fire-breathing dragon was seen in Beaver County on its way to Ohio. (This line would become the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago, then the Pennsylvania Railroad, then the Penn-Central, and now Conrail).

The railroads didn't kill all of the canals right away. The C & 0 Canal endured until the 1930's, even though it ran side by side with the B & 0 railroad along the Potomac. Coal was the difference. Where there was much coal to be hauled, the canals could compete.

The Beaver and Erie died a quick, merciful death. Though twenty years had passed since the railroads came to western Pennsylvania, much freight was still being hauled by water. Then, in 1872, a high aqueduct that carried the canal over the deep gorge of Walnut Creek in Erie County collapsed into the valley below. The shaky financial condition of the privately owned canal company precluded any possibility of repairs. Thus the canal era in western Pennsylvania ended suddenly, without the slow lingering disappearance that others were to endure. Within two years, all traces of the canal were covered up in the city of New Castle. In that same year, the last boat reached Moravia (West Pittsburgh). The Girard Locks in Rochester, built large to accommodate small steamboats, served the lower Beaver Valley until, in 1901, the last load passed through. This was a raft of logs for the keg works in New Brighton, which was built on top of the Blount Lock. The Girard Locks remained in good condition until about fifteen years ago, when they were filled in for construction of a sewage pump station.

Three times in this century; the Beaver and MahonIng valleys have been surveyed to determine the feasibility of building a canal from the Ohio River to Lake Erie. The latest effort, in the 1960's, was defeated in part by Pennsylvania interests who were loathe to provide their competition in Youngstown, Ohio, with better transportation facilities. In another generation, the survey is likely to be run again, and perhaps some day .....