Grover Schuster's Gasoline Station Beaver Falls

The north end of Beaver Falls had a business section all its own. There were several grocery stores and meat markets and other businesses in an area that extended from about 22nd to 26th streets and from Seventh to 10th avenues.

In fact there was an organization called the North End Business Men's Association that was one of the most powerful merchant groups, not only in the city but in the upper valley.

Pictured above is the gas station owned by Grover Schuster at 24th Street between Eighth and Ninth avenues. The photograph was taken in the mid-'20s. Schuster went into the gas business shortly after World War I. He was a veteran of the war and had a family history of business, especially in groceries and meats.

In the photo is Frank Laird, Schuster's brother-in-law, pumping gas while Schuster, in a white shirt, stands under the gas pump canopy. Gas stations dealt in all auto accessories including tires - in this case Tiger Foot tires which cost $6.95 each.

The little white building to the right of the main store was a restroom. The white building adjacent to it was for supplies including oil and kerosene. Later, garages were added that obscured the home on the right.

Schuster also operated a grocery store and meat market in a building on the corner of the above site. When Jackson Hardware on Eighth Avenue went out of business, Schuster began selling hardware at the request of his customers.

At age 65, he closed his business. He died at age 87 in 1979. His widow, Ann Laird Schuster, now 87, resides with a son, Woodrow, who operates a used furniture store at the grocery store site. A daughter, Mary Jane Braheny, South Beaver, is a teacher in the Western Beaver School District. A son, Warren, died in February 1984.

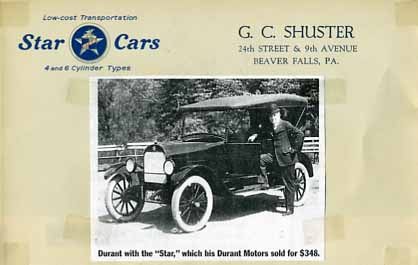

For a period of time, Grover Schuster sold the Durant Star Car.

During one week last summer the stock market suddenly soured on technology stocks. Microsoft's William S. Gates saw his fortune decline by an awesome 2.4 billion dollars. To get some idea of just how much money that is, consider that if a person had a net worth that large, he or she would rank about number twenty-two on the Forbes Four Hundred list, right alongside the likes of Ross Perot. Of course, Bill Gates is not number twenty-two; he is number one, so the wolves remain many billions of dollars away from his front door. Still, that is probably some sort of record for short-term paper losses.

For short-term real losses, however, the record is almost certainly held by William C. Durant. Between April and November 1920 he lost ninety million dollars, well over a billion in today's money. Had there been a Forbes list then, he would have gone from near the top to the edge of bankruptcy in less than eight months. Ironically lie suffered these real losses in a hopeless attempt to prevent mere paper ones.

Of all the major figures in the history of the American automobile industry, none, not even Henry Ford, compares with Durant for the sheer drama of his career. (Tile best full-length biography of him, The Dream Maker, is by one of my colleagues in the front of this magazine, Bernard A. Weisberger.) Durant would scale the heights of capitalism by creating General Motors. But he would end his days running a bowling alley.

Durant was born in Boston in 1861 of old New England stock. His maternal grandfather had moved to Michigan, prospered mightily in the lumber trade, and served as the mayor of Flint and as Michigan's governor. When Durant's parents' marriage collapsed after his father bankrupted himself in the wild stock market of the late 1860s -his mother moved back to Flint.

Leaving high school without bothering to graduate, Durant was soon working for a local cigar manufacturer as a salesman. When he returned from his first sales trip, his boss was furious to learn that Durant had run up travel expenses of $8.15 in only two days. The employer, however, decided not to make an issue of it when Durant turned in orders for no fewer than twenty-two thousand cigars.

While many of his contemporaries were still in school, Durant had already found the wellspring of his genius. He was a natural-born salesman. His philosophy was simple: "Let the customer sell himself," he said. "Look for a self-seller. If you cannot find one, make one."

Following his own advice, he quickly found a self-seller and decided to make it. When he was twenty-four, a friend offered him a lift in his new cart. Durant discovered that the cart did not bounce the passengers around the way most sulkies did. He inspected it and saw that the reason was a unique suspension system.

Durant recognized a winner immediately. He tracked down the manufacturer and, for fifteen hundred dollars he didn't yet have, bought the patent rights and took in a partner to provide working capital. The company was an immediate success, and by 1900 Durant Dort was the largest carriage company in the United States.

Durant was a very rich man, but the carriage business was beginning to bore him. He needed new challenges. In 1900 it was still possible to believe in a prosperous future for the horse-drawn carriage business, but Durant noticed that when he drove an automobile around Flint, he collected a fascinated crowd wherever he stopped. Durant had a self-seller; he just had to make it.

Automobiles had been around since the early 1890s. But they remained largely the product of back-yard tinkerers, most of whom had no conception of what was needed to make a successful automobile business. Durant did: capital and lots of it. He quickly proved as able at selling stock as he was at selling everything else.

In 1904 Durant took over management of the Buick Motor Company, which had moved to Flint the previous year and was in financial extremis. He displayed a model at the New York Automobile Show that year and immediately took orders for 1,108 cars, despite the fact that this was more than twenty-five times the total number of cars the company had manufactured since its inception.

Spured on by this success, Durant went on to form his own car company which eventually led to his demise.