Click Here to Return to Milestones

The great social movements of the nineteenth

century changed the character of this nation. Among these movements

were abolition, women's suffrage, temperance, improved labor conditions,

cooperative communities (association), educational and prison

reform.

Of these the most dramatically successful in that century was

the effort to free the slaves. Antislavery organizations provided

lecturers such as William Lloyd Garrison, Abby Kelley, Stephen

S. Foster, Frederick Douglass, Charles Lenox Remond, and Wendel

Phillips.

The importation of slaves from Africa to the United States had

become illegal in 1808. The invention of the cotton gin in 1793

by Eli Whitney increased production tenfold and thus the need

of more slaves. The number of slaves increased from about 1.5

million in 1820 to more than 2 million or almost one-sixth of

the population in this country by 1830. At the same time there

was a free black population numbering about 320,000 by the end

of the 1820s. Three-quarters of the world's cotton was produced

in the South by slave labor in 1860. Cotton and the attendant

cotton mills in the North were the driving forces of slavery.

At this time a cotton mill was operating in Beaver Falls.

In the earlier years of the movement the abolitionists believed

that the churches as well as respectable and influential people

and leaders of communities would support them in the North and

shame the South into abolishing slavery, and they suffered intense

disillusionment when this help did not materialize. Not only did

the church, businessmen, and other leaders refuse to support the

cause in any way, but they opposed it vigorously. Opposition to

the antislavery movement became violent.

In the 1830s much of this violence, especially the well orchestrated

riots against the antislavery press and leaders, spread across

the northern states as its organizers sought to destroy printing

presses that supported the movement and to intimidate free blacks.

The leaders and organizers of these riots were the very people

from whom the abolitionists had expected support, such respected

citizens as lawyers, bankers, doctors, and political leaders from

both parties.

In 1835 introduction of the steam press and other new technology

decreased the cost of publication and made greater volume possible,

enabling abolitionist newspaper editors, writers, and lecturers

to take advantage of mass communication. That year the Anti-Slavery

Society was able to distribute 1.1 million pieces of literature

in contrast to 122,000 the previous year. One result was that

antislavery societies in the United States increased from about

200 in 1835 to 527 in 1836.

In 1850 the Fugitive Slave Law, which required federal agents

to find escaped slaves in the North and return them to their Southern

owners, was passed. It provided a penalty of $1,000 to anyone

aiding in a slave's escape. As a result Federal agents kidnaped

blacks who appeared in the streets of Northern cities. Bounty

hunting became a lucrative business. Those actively involved in

helping runaway slaves were forced into civil disobedience in

defiance of this law.

There is an interesting local story of a fugitive slave living

in Beaver County. Mr. Richard Gardner(aka Woodson), formerly owned

by Rhoda B. Byers of Louisville, Kentucky, settled in Beaver and

lived there for two years. Gardner, a well-respected black man,

built a house in Beaver and was preaching to a Methodist congregation.

He and his wife would walk to Bridgewater to the hotels at the

steamboat landings to pick up laundry.

He was lured one day to a landing where he was arrested by a federal

agent and two residents of Beaver. He was not allowed to say farewell

to his family but was taken to a boat waiting on the Ohio River

and taken to Pittsburgh for trial. There he was tried, found guilty

of being a fugitive slave, and returned to Rhoda Byers.

Citizens of Beaver were so outraged by these acts that they started

a fund to buy his freedom. It took $600 and two years to bring

Mr. Woodson back to his family. He returned to Beaver in 1851

and lived a free man until his death in 1876.

Abolitionists pointed out to all who would listen or read that

slavery was a moral problem. This viewpoint increasingly found

its way into the consciousness and consciences of many who listened

to antislavery speakers, read their publications, and discussed

the issue with family and friends. In 1850 such awareness was

also helped forward by the enormity of the Fugitive Slave Law.

The movement grew.

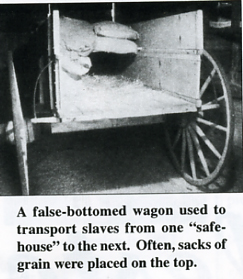

The name, Underground Railroad, is itself deceptive. It was neither

underground (with some exceptions), nor was it a railroad. The

name alluded to the clandestine arrangement made by those who

helped slaves escape from the South to freedom in Canada.