Arthur Bradford and his wife, Elizabeth.

Click Here to Return to Milestones

On Wednesday, December 1, 2004, Buttonwood,

home of the noted abolitionist, Arthur Bullus Bradford, was sold

at auction to Bradford Wilkie, senior software engineer at Carnegie

Mellon, for $260,000. This brought to an end generations of Bradfords

who had occupied this land.

Arthur Bullus Bradford, a direct descendent of Governor William Bradford of Mayflower fame, purchased the Buttonwood property in the late 1830s and built the house in 1840 from bricks made of clay found on the farm. That house continued in the family until the December 1, 2004, auction, a matter of 164 years.

Arthur Bullus Bradford, born at Reading, Pennsylvania,

March 28, 1810, was the son of Judge Ebenezer Green and Ruth Bullus

Bradford.

Arthur attended Princeton Seminary, where there

were those who were advocating the African Colonization Plan for

the black man. But Bradford, even as a student, thought the plan

impracticable and was convinced that the question must be settled,

not in Africa, but in America.

While still a student he preached to and talked

with a number of black citizens in Philadelphia. In addition to

this, his vacations were spent on the Maryland plantation of an

uncle, Moses Bradford, in which state he saw slavery firsthand.

He gave much thought to the question of slavery; and as he mused,

the fire of indignation against the institution began to burn

fiercely in his soul. And so a great abolitionist was born.

Bradford was licensed by the Presbytery of

Philadelphia, April 16, 1834.

On Tuesday, May 10, 1836, he married Elizabeth

Wickes (December 17, 1812-April 9, 1891).

In 1839 he was installed as pastor of the Mt.

Pleasant Presbyterian Church at Darlington, Pennsylvania.

In 1799 Mt. Pleasant Church had obtained the

Rev. Thomas E. Hugues as pastor, at first sharing him with New

Salem Presbyterian Church. Hughes, also a renowned schoolmaster,

had established the Old Stone Academy known today as Greersburg

Academy and the Old Stone Pile.

In 1847 Bradford and a number of ministers

renounced the authority of the Presbyterian Church, withdrew from

it, and founded the Free Presbyterian Church. The declaration

of this renunciation was made by Bradford and the Rev. S. A. McLean

at the June meeting of the Presbytery of Beaver, held at North

Sewickley. The reason for this secession was dissatisfaction with

the stand of the Old School General Assembly of the Presbyterian

Church on the question of slavery particularly with the action

of the General Assembly of 1845, which declared that slave-holding

was not a bar to Christian Communion. The Presbytery, through

its Stated Clerk, told Bradford and McLean that their names were

to be removed from the roll. Further it was said that "they

have greatly erred and greatly sinned."

Bradford published the following prophetic

words in the November 1859 issue of his Free Church Portfolio:

"The duty of the Free Presbyterian Church is plain. It is

to stand in her lot bearing her testimony against the great sin

of our country. The principles are spreading all over the land

and, being right, must ultimately prevail."

In 1847 in Darlington a beautiful place of worship was built to house the Free Presbyterian Church. With the elimination of slavery, however, the Free Presbyterian Church disbanded in 1867, as its raison d'etre had evaporated. The congregation then joined the Reformed Presbyterian Church in North America.

Dr. Clarence Edward Macartney, then pastor

of the First Presbyterian Church of Pittsburgh, wrote an article,

"Buttonwood and a Great Abolitionist," which was published

in the Princeton Seminary Bulletin. In it he covered Arthur B.

Bradford's life and activities to a great extent and provided

an especially helpful account of Buttonwood. The following is

from that article:

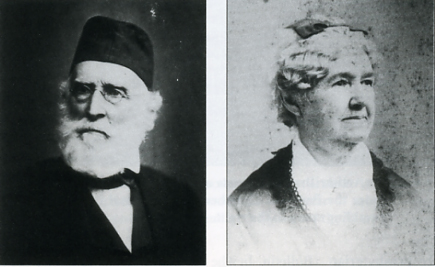

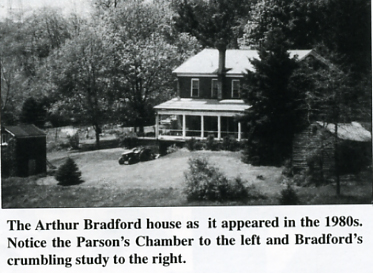

"Bradford' splendid old home is still

standing, a little to the south of the main road leading from

Darlington, Beaver County, PA., to Enon. It derives its name,

"Buttonwood," from a gigantic buttonwood tree which

still stretches out its arms just back of the "Prophet's

Chamber." This two story brick building was used for visiting

clergymen. It was built to suit the needs of itinerant preachers,

and especially visiting Abolitionists, for many a conference of

noted Abolitionists was held at "Buttonwood."

The house...is a noble brick mansion with a

southern outlook. A covered porch runs the whole length of the

house on that side, and you can think of Bradford sitting on that

porch as the sun was westering and discussing the burning questions

of the day with the leading Anti-Slavery agitators: Parker Pillsbury,

Abby Kelley Foster, Joshua R. Giddings, the most noted Anti-Slavery

man in Congress, and, no doubt, Fred Douglass..., the orator,

Sojourner Truth,... and John Brown of Ossawatomie, Kansas.....

In the kitchen is a tremendous stone rimmed

fireplace, where in the first days, before stoves were available,

the cooking was done. Not far from Bradford's farm, beds of the

famed Cannel coal were first opened in 1839, two years after the

building of the house and this coal, superior to the ordinary

bituminous coal, cooked its food and heated the rooms in the Bradford

home.

Not far from the main entrance to the house stands an odd little frame building. This was Bradford's study. His study was first in the main house, but when the Lord "multiplied his mercies upon him" to the number of nine [sic.] children, he thought it was time to move out and have a study remote from the clamor of his offspring. There it was that he wrote the sermons he delivered in the church at Darlington, and the editorials and leading articles. Bradford was a powerful pamphleteer, and articles from his pen appeared in many of the religious periodicals and Anti-Slavery magazines of that day...."

During the years before the Civil War Arthur

Bradford became very much involved in the antislavery movement.

He lectured across western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio in practically

every village as well as in Boston and New York and as far away

as Iowa. It is reported that he was such a dynamic and effective

speaker that he held his audiences in enthralled silence.

He did not, of course, limit his antislavery

activity to making speeches. He wrote abolitionist materials for

the Beaver Argus, William Lloyd Garrison's Liberator, the New

Castle Courant, and various Pittsburgh newspapers.

Among his abolitionist friends and acquaintances

were Joshua R. Giddings, Wendell Phillips, William Lloyd Garrison,

Abby Kelley, and Sara Jane Clarke (well known as the author, Grace

Greenwood).

Sara Jane Clark, in a February 17, 1844, letter

from New Brighton to Milo Townsend, writes, "The noble band

of Abolitionists have almost overwhelmed me with unnumbered kindnesses....My

communications have been politely received, and I think I can

already count some gentlemen of the antislavery press among my

friends.... Mr. Bradford of Darlington has manifested a flattering

interest in my antislavery progress." Abby Kelley and Sara

Jane Clarke spent a summer at Buttonwood. Another of his friends

was Milo Adams Townsend of New Brighton. Milo and other members

of his family, notable Quakers of that place, was very actively

engaged in caring for fugitive slaves and arranging their transport

to Buttonwood. In addition, like Bradford, he was a prolific antislavery

writer, publishing his articles in Beaver Valley newspapers, Pittsburgh

papers, The Anti-Slavery Bugle, and, of course, Garrison's Liberator.

Milo, as a bookseller, sent Bradford some books with a bill and

as a postscript, the coded message, "How moves the Car of

Progress? There are too many Brakemen on the train to attain much

rapidity, I fear." The "Car of Progress" is the

underground railroad, and the brakemen were those who from time

to time stopped the "train" and captured the fugitives.

This relationship between Bradford and Milo was the beginning

of the friendship between the Bradford and Townsend descendants

that has continued into the 21st century.

Participating in the work of the underground

railroad was potentially very dangerous. The Fugitive Slave Law

provided the penalty of a $1000 fine for anyone convicted of helping

these slaves to escape. To protect his wife and children from

losing their home, Bradford transferred his property to a friend,

who was faithful to his trust, and Bradford lived at Buttonwood

until his death in 1899.

As on his lecture tours especially Bradford

was liable to meet with hostility, the Philadelphia Anti-Slavery

Society gave him a sword cane to defend himself if the need should

arise. Although even some neighbors with Southern sympathies threatened

to tar and feather Bradford, no one ever harmed him physically;

and he did not need the cane, which remained at Buttonwood for

many years after his death.

The underground railroad station at Buttonwood

was very busy. It formed a link in the route north to Canada from

New Brighton and Beaver Falls to Enon Valley and thence west through

Salem, Ohio, and north. The Bradford home, situated only a few

rods from the old stage coach line leading from Beaver to Cleveland

and a little concealed from sight by the contour of the country,

was an admirable site for the arrival and departure of fugitives.

In a 1930 interview, Mrs. Hardy(who lived at

Buttonwood) said she saw many fugitive slaves lined up along the

fence in front of the house of a morning, waiting for their breakfast

before passing on to Salem, Ohio, the next station. Slaves were

brought from New Brighton, sometimes 8 or 10 at a time. They were

fed and sheltered until they could be secretly transported to

another underground station. This was often done at night and

with personal danger since it was against the law to aid runaways.

The frequently needed clothing to disguise

runaways was made by Bradford's daughters, who often used their

own dresses to fashion these costumes.

Marjorie Douthitt(a great-granddaughter of

A. B. Bradford) was told that at one time such a very tall fugitive

arrived that the women of the household stayed up all night sewing

cloth together from two or three of their own dresses to make

one for him. They also fabricated a big sunbonnet to hide his

face. The worst problem was shoes. His feet were huge, and the

Bradfords apparently never did find any to fit him, in the end

probably making the dress long enough to hide his feet.

Marge Douthitt has never been able to find where the fugitive slaves were hidden. Charles W. Townsend II told her that they were hidden in a coal mine on the hill. The mine had caved in by the time Marjorie came to Buttonwood as a girl of fifteen, so she never saw inside it.

Arthur was away from Buttonwood for about two years beginning in 1861 when Abraham Lincoln appointed him the U.S. consul to Amoy, China. To act as hostess in his home, his twenty-year-old daughter Ruth accompanied him to China aboard the Julia G. Tyler, a trip that began at New York City between September 8 and 10, 1861, and ended at last in China April 17, 1862, after a voyage of seven months and two weeks. Arthur's son Oliver also accompanied his father. When illness drove Arthur to leave his China post, Oliver became his replacement and continued there for twenty years.