Return to Milestones Vol. 2, No. 4

The steel industry so dominates Aliquippa that the record - and evidence - of other early industry is all but lost and forgotten. The land included in the present-day borough limits did experience, however, a gradual development of agriculature-related industry and a significant move toward manufacturing before the sudden transformation of a rural village into the home of one of the world's largest steel plants.

If we consider agriculture an industry, Aliquippa's record predates the rest of Beaver County. In 1752, Christopher Gist, an agent for the Ohio Company of Virginia, attended a treaty conference at Logstown Indian Village. In his journal, he describes unharvested fields of corn across the river. This report of primitive cultivation is the earliest on record for any productive use of the land of Beaver County.

In 1771, Col. John Gibson, one of Aliquippa's earliest residents, cleared and planted his three hundred acre tract. This was described in the journal of Rev. David McClure, who visited Gibson in 1772.

Logstown Bottom, as the downtown area was known, and White Oak Flats, or New Sheffield, were to see little more than agriculture -- and related industries-for the next century and a quarter.

Possibly the earliest record of manufacture of retail goods in the future Aliquippa might be the distillery which operated briefly opposite Gen. Anthony Wayne's encampment at Legionville, in 1793, and attracted the trade of the troops until Wayne discouraged the enterprise with cannon fire. It is likely, however, that distilling spirits was common in the area prior to this time, since the excise lax imposed the following year led to the popular uprising known as the Whiskey Rebellion, and involved farmers from Allegheny and Washington Counties.

The grain that wasn't distilled had to be ground for flour, so the grist mill, usually water-powered, is most often the first industry in any developing area. Beaver County's earliest industry was White's Mill, a landmark on Raccoon Creek in Independence Township not too far from Aliquippa. This mill is mentioned in the boundary description of Beaver County, and its location determined the southeastern corner of the county, attesting to the importance accorded to grist mills when this was the western frontier.

In the years following, the waters of Logstown or Jones' Run would have provided a number of mill seats. Weingartner's 1832 map of Beaver County shows McDonald's Mill in Logstown Bottom. Andrew McDonald, minister of White Oak Flats Church, was Logstown's earliest permanent settler (around 1810).

Woodlawn's early historian A. R. Temple cites Anderson's Mill at New Sheffield, but this was on Trampmill Run in Hopewell Township. Temple places Elisha Veazy's Mill on Sheffield Terrace, but early maps show that it also was on Trampmill Run, along Kane (Cain) Road. He reports remains of Todds Mill at Elk's Park, which was located off Kennedy Boulevard below Plan 12, but further documentation has proved elusive. A steam powered feed mill was operated at Brodhead and Mill Street in New Sheffield by Bickerstaff and Kaste in the early years of the present century.

The manufacture of hardware necessary for agriculture is generally accepted for the period prior to 1800 in Beaver County. Temple cites two sickle factories operating in this period, including one, Thomson's, near New Sheffield.

The name Woodlawn was first applied to the downtown Aliquippa area in 1877 by Mattie McDonald, in search of a name for the new post office, of which her husband, C. 1. McDonald, would be postmaster. Prior to this time the area was known as Logstown Bottom.

Woodlawn Village( Sheffield Avenue) around 1908. At left, the new Pittsburgh Mercantile Company Store. Next to it, the Woodlawn Presbyterian Chruch and, behind the tree, the Woodlawn Academy.

This was coincidental with the arrival of the Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad, which crossed Logstown Run on a huge trestle and began regular passenger and freight service in 1878. The railroad brought little immediate change to Woodlawn Village. A man named Iver opened a blacksmith shop in 1878. Already operating in this area was McDonald's Saw Mill on Logstown Run.

A glue factory was located on the Presser farm along the river opposite Economy. This summary of' industry in the village of Woodlawn seems exceptionally primitive in light of the extensive diversified industrial complex at the Falls of the Beaver at the same time,' and the fact that note-worthy boatyards were in operation fifty years earlier in the neighboring communities of Monaca, Freedom, and Shousetown (Glenwillard). But Woodlawn wouldn't always be an agricultural community.

Aliquippa Park appeared around 1880, shortly after the completion of the P. & L. E. Railroad. The park, along Jones Run, was typical of the railroad attractions of the period and, viewed as an example of the recreation industry, was undoubtedly the largest employer in the area. This was the first use of the name Aliquippa for this vicinity, and leads one to conclude that the Aliquippa Borough of the future was named not for an Indian Queen, but for an amusement park. A visitor in 1900 described the facilities in Aliquippa Park as follows: baseball fields, tennis courts, a merry-go-round, a laughing gallery, a dance hall, toboggan slide, photo gallery, dining hall and restaurant. The complex also included a power house and superintendents's office. The dance hall survives as the second floor of the central part of the Jones and Laughlin plant, having been moved by railcar after J & L purchased the park as part of the future plant site.

The village that grew up around the park became known as Aliquippa, and soon had its own railroad station of the same name. In 1891, the Russell Shovel Company located here, and the townsite that would become the first Borough of Aliquippa was laid out. The areas first lumberyard was established in 1892 by the Cochran Brothers. Aliquippa acquired a Post Office in 1892 and was incorporated in 1894. Shortly after the turn of the century, another major industry located there, the Vulcan Crucible Company. Vulcan employed about one hundred and fifty men in its early years and produced high grade tool steel. The plant, as constructed in 1901, occupied eight acres and included a fifteen ton open hearth furnace, a thirty pot crucible melting floor, two annealing furnaces, four forging hammers, and two rolling mills. In 1916 and again in 1926, electric furnaces were installed, replacing the crucible and open -hearth furnaces. In 1928, Vulcan purchased the Russell Shovel Company.

In the meantime, other industries came to Aliquippa. The Aliquippa Brewery was built in 1905, and thrived on native thirst until the Volstead Act. The truncated building remains today as a J & L warehouse at the southwest corner of town.

In 1914, the Kidd Drawn Steel Company built a plant next to the Vulcan Crucible Office. Kidd, founded in McKee's Rocks in 1897, made quality rod and wire products.

Vulcan signed its first contract with the steelworkers union in 1944. In 1955, it was acquired by the H. K. Porter Company, and continued to operate as a division of the parent company. In 1958 Porter purchased Kidd Drawn Steel, and formed the Vulcan - Kidd Division of H. K. Porter. Both plants were shut down in 1965 after extended negotiations failed to produce a contract with the union. In subsequent transactions, Vulcan became the Forge Shop Division of Universal Cyclops Specialty Steel Company of Pittsburgh in 1966. In the same year, the Precision Grinding Company of Washington, Pennsylvania purchased the Kidd Plant, which continues to operate as Precision-Kidd, Incorporated, with a majority of its former employees.

While Aliquippa was transformed into a mill town, Woodlawn remained a quiet farming community. The Woodlawn Academy, founded in 1879, offered a secondary education to young people from Logstown School District (of Hopewell Township) and surrounding communities. Some trade was attracted to the village by the ferry to Legionville, in operation after 1866.

The canalization of the Ohio River affected the village as construction began on Lock and Dam No. 4 at the mouth of Logstown Run in 1905. Then, in that year, Woodlawn became a Cinderella town. The fairy godmother was the Jones & Laughlin Steel Company and the transformation was magical. Instead of leaving the cinders behind, however, the cinders were in the future for Woodlawn.

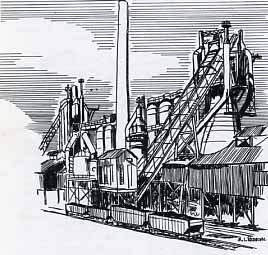

Land purchases were completed in 1905, grading for the plant in 1906, and construction started in 1907. A financial panic in that year delayed construction, but the first blast furnace began producing iron in December of 1909 and two more were in blast the following year.

The same five year period saw a swampy creek bottom transformed into a paved business thoroughfare with a five story department store and many other buildings.

Logstown Valley and the surrounding terraced hillsides had been divided into twelve "plans", and construction of homes in Plan 1 began in 1907 and in Plan 12 by 1912.

The plant itself was built in such a hurry that the company's main office was a transplanted dance hall, and that of the subsidiary Aliquippa & Southern Railroad was the Doud's farmhouse that just happened to be in the right location.

It was a company town. J. & L. owned the water company, the land company, and, in 1912, the Woodlawn & Southern Street Railway Company. Schools were built. One in 1910, five more by 1919. Churchesof many denominations -- Roman Catholic, Methodist, Baptist, Episcopalian, joined the existing Lutheran and Presbyterian congregations in old Woodlawn. These were quickly followed by new and "strange" religions -Ukrainian Orthodox, Russian Orthodox, Greek Orthodox, Serbian Orthodox, and Jewish and African Methodist congregations. This was the biggest change for the people of Woodlawn Village. Suddenly, there were "foreigners" in town. There was little communication between the old and the new residents, little understanding of their customs, their words, their thoughts, their desires, their dreams. Relegated to second class status in town, the newcomer was respected only in the heat of the mill, where he could work as hard or harder than any Scotch-Irish man on the crew. Time would pass, however, and these people would have their day. Modern America was built on hybrid vigor.

Woodlawn was incorporated as a borough in 1908, and grew rapidly up the valley of Logstown Run. By 1925, distant New Sheffield was within the borough limits. In 1928, Woodlawn was ready for its big conquest. A merger was proposed between the overgrown giant of Logstown valley and its awe-stricken neighbor to the north, Aliquippa. In an election where residents of old Aliquippa still claim that nobody voted for the merger, both communities approved the move -at least officially -- and the present community of Aliquippa was born. Adoption of the name of the smaller partner was no concession to that town, it was a mirror reflection of the overwhelming influence on the riverbank. The Aliquippa Works of J. & L.

The growth of the steel mill is a legend in itself. From that first blast furnace in 1909, the production facilities expanded in all directions. In a well-planned expansion that is still continuing, J.&L. moved into steel production, then developed many ways of preparing the steel for specific uses by the customer.

By 1919, five blast furnaces were producing one million tons of pig iron each year. The first of five open hearth furnaces was producing steel by 1912, and three Bessemer converters were adding to steel production by 1916. To support the tremendous appetite of these furnaces, four hundred and eighty-eight coke ovens were producing half a million tons of coke per year in 1913. A similar amount of limestone and three times as much iron ore were consumed annually.

From 1916 to 1920, the plant added a skelp mill two buttweld pipe mills and three lapweld mills, with a combined capacity of three hundred thousand tons of finished pipe per year, from one quarter inch to fifteen and one half inches in diameter, of various grades.

The first rod mill started in 1910, followed by wire mills, nail mills, fence mills, tin plate lines, and the fourteen inch rolling mill for bars, angles, and special shapes.

In 1921, the first river tow of steel products, The Steel Argosy, was sent down river to New Orleans. This indicated that it was no coincidence that J. & L.'s expansion to Woodlawn occurred simultaneously with improvement of navigation on the Ohio River.

Nineteen twenty-three brought significant changes. J. & L. incorporated and sold its stock on the open market. The American Iron and Steel Institute eliminated the twelve hour working day. For J.&L's seven to eight thousand employees, this meant an eight hour, six day work week, with more time for recreation and family life. The company provided swimming pools in various parts of the borough, and B. F. Jones' daughter donated a library.

In the late twenties, steel production soared as the automobile became the leading consumer of steel. Blast furnace capacity was increased in 1930, and again in 1966. The population of Aliquippa peaked at over twenty-seven thousand in the thirties, the biggest community in the county. Serious problems existed in the town, however. The coal and iron police used brutal tactics to terrorize anyone who "stepped out of

line". Voter registration and elections were rigidly controlled by company agents. Aliquippa was described as "Little Siberia" by Mrs. Gifford Pinchot, the wife of the governor of Pennsylvania.

All this would soon change, however, in 1937. Following a long strike and numerous court battles, the Steelworkers Union finally won recognition and a contract from the company. This was just in time, for World War 11 broke out a few years later.

The company and union worked together in this crisis to set and reset world production records on No. 3 blast furnace and the Blooming Mill, winning for the Aliquippa Works the Army - Navy "E" Award for outstanding efficiency.

The war ended, and a series of strikes followed, as the union and company attempted to reach an equilibrium. Expansion continued, and in 1948, J. & L. built the worlds fastest steel rolling mill. At the same time, the company continued to recognize its obligation to the community, and donated land in 1948 for a baseball field and picnic ground. In 1957, the company and the community worked together to build a hospital, just in time for the borough's Golden Jubilee celebration in 1958.

That year saw a revolution as J. & L. installed the first of five Basic Oxygen furnaces, and started phasing out the open hearths and Bessemer converters. New techniques for producing pipe were introduced with electric weld and continuous weld lines. Employment at the Aliquippa Works reached a peak at over thirteen thousand.

In 1968, the old Crow Island at West Aliquippa was filled in and more Basic Oxygen furnaces were erected. In that year J. & L. was acquired by the Ling - Temco - Vought Corporation. In 1974, Jones & Laughlin announced a two hundred million dollar expansion program for the Aliquippa Works, which is still underway.

Today, the Aliquippa Works of the Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation occupies six and one half miles of riverfront, and seven hundred and twenty-seven acres. Fifty major buildings provide employment for eleven thousand men and women. The Aliquippa & Southern Railroad, operating mainly within the plant, has ninetyone miles of track.

Other industries in modern-day Aliquippa are largely related to the steel mill. Air Products, Inc. operates on the plant site to generate oxygen for the steel furnaces. Duquesne Slag Company disposes of the continual by-product of iron-making.

A 1954 report of the Pennsylvania Economy League listed twenty-six diversified industrial and manufacturing establishments in the Aliquippa area. Inevitable changes have occurred in twenty-two years, but in general, the following list describes the industries of Aliquippa in the post war period: manufacturers of concrete products, food, soft drinks, ice, metal products, mine and quarry products, paper and printing, textile products, etc.

Despite generally good employment in Aliquippa over the years, other factors have generated a move to the suburbs and a serious decline of the downtown business district. Many of the factors which contributed to the deterioration of the community should have been recognized when they were minor problems twenty, thirty, fifty years ago. Is the process reversible, or has the world changed too much to give Aliquippa a second chance?